UK Markets 2022

1. BNG

1.1 THE BIODIVERSITY NET GAIN MARKET

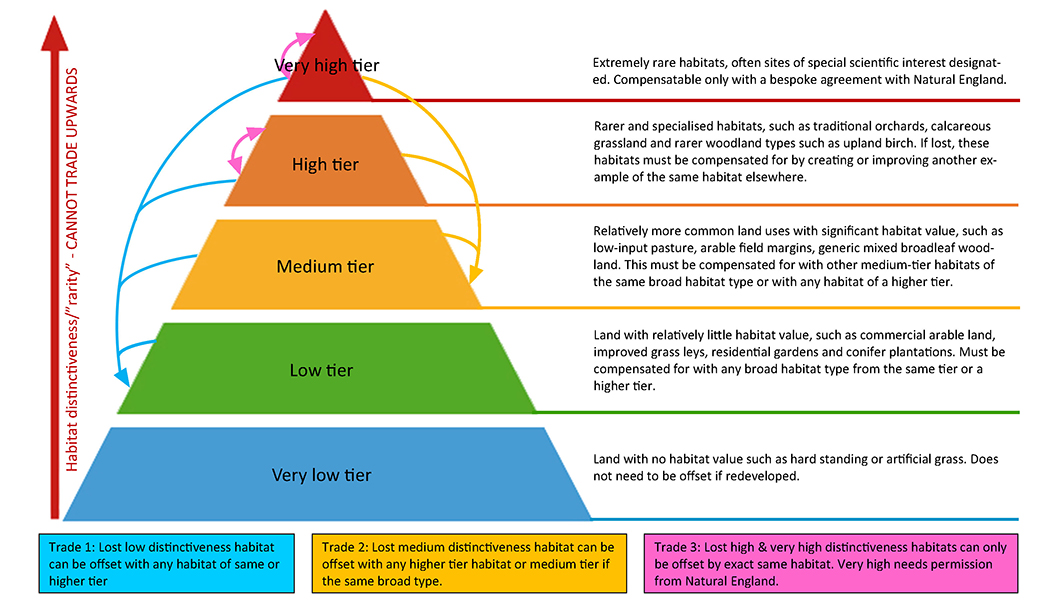

TCS Habitat Distinctiveness/”Rarity” and Trading Pyramid

1.1.1 The new Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) market, contrary to early expectations, is an England-wide market. Why this is and how it works is explained here.

1.1.2 One of the most common misunderstandings about the English Biodiversity Net Gain market is that the marketplace for any particular units created will be restricted to within the same Local Planning Authority (LPA) or the adjoining one. This confusion comes from two already well-known factors. The number of units sold outside their own LPA will be reduced by the “spatial risk multiplier” and developers are obliged to acquire compensation for lost units in the same LPA before they are able to buy units from further afield. If these were the only factors affecting BNG, the market would be similar to the Water Abstraction Licence market with hundreds of totally separate markets for each water catchment area.

1.1.3 However on closer inspection there are other factors that mean when looking at selling any BNG units one could be missing out on higher achievable prices if not offering them nationwide.

1.1.4 We are now familiar with exactly what BNG is aiming to be. BNG is the improvement in a habitat’s condition or the creation of new habitat to provide the equivalent of a 10% net gain in biodiversity value. If this cannot be achieved on the development site then developers may pay farmers and landowners to improve their land, this allows developers to meet what will become a statutory requirement for every type of development requiring planning permission.

1.1.5 However, there is some complexity as to how the different types of “net gain” compare with one another. Our Habitat distinctiveness/“rarity” Pyramid illustration above should be read from the bottom up.

1.2 TERMS USED

1.2.1 Broad habitat type

What the Government calls “broad habitat type” means the general category of land in question. There are 15 options for this in total, including woodlands, hedges, “cropland” (i.e. arable), grassland, urban, heathland, wetland, ponds, rivers and a few rarer options such as “sparsely vegetated land” and “intertidal hard structures”.

1.2.2 Habitats

Land within a “broad habitat type” can be one of a number of possible “habitats” which fall within the broad habitat type. For example, “grassland” as a broad habitat type includes, among other options, commercial ryegrass pasture (“modified grassland” in government language), semi-natural “lowland calcareous grassland”, and traditional hay meadows. Exactly which habitat is on a piece of land is set by the number and species of plant which are growing there.

1.2.3 Distinctiveness

1.2.3.1 Different habitats are split up by “distinctiveness”. This just means how rare and valuable the habitat is. Distinctiveness has five tiers, each represented by a layer of the Pyramid. Lower distinctiveness habitats are worth fewer BNG units and are simpler to replace; higher distinctiveness habitats are worth more units and the procedure for replacing them is more complicated. Habitats of different levels of distinctiveness are tradeable in different ways.

1.2.3.2 There are two ways a landowner can earn BNG units. One is to improve the “condition” of existing habitats. We do not cover this “improvement” here.

1.2.3.3 Alternatively new habitats that are of higher distinctiveness than the existing habitat can be created. What this means is moving the land from a lower tier of the Pyramid to a higher one. If you start with an intensive pasture field and stop ploughing and spraying it so it becomes an “unimproved” pasture the field will move up from the “low-distinctiveness” tier to “medium-distinctiveness”, which means you will have created units to sell.

1.2.3.4 Cannot replace a lost habitat with a habitat of lower distinctiveness – An important rule is that a lost habitat can never be replaced by habitat of a lower tier. In theory, if even a few square feet of mixed woodland, a “medium-distinctiveness” habitat, was lost to a development, the developer could not go ahead even if they committed to turning, say, all of a 30ha disused power station into a commercial conifer plantation (ignoring any of the broadleaf and open space areas which are always included in modern commercial planting). This is because commercial conifers, while more distinctive than the disused power plant, are less distinctive than the lost mixed woodland, so cannot replace it regardless of how much area they cover. They would instead in this example need to arrange for the planting, or improvement, of another woodland of medium distinctiveness or higher. It is not just a question of how large an area you replace a lost habitat with, but what distinctiveness the replacement is.

1.3 THE PYRAMID TIERS

The tiers of the Pyramid from bottom to top are:

1.3.1 “Very low” distinctiveness

1.3.1.1 These are areas which the Government does not think have any biodiversity value at all. Examples include AstroTurf, hardstanding and concreted areas. They have no value in terms of BNG credits – “Brownfield Sites”.

1.3.1.2 That means that they do not need to be replaced or compensated if they are lost when redeveloped and also that creating these areas will not gain you any biodiversity units. This appears logical – it seems absurd to create a new parking area or a modern farm building for wildlife reasons.

1.3.1.3 For example, if a developer were to build a new commercial building on the site of a recently disused petrol station, they may not need to purchase any BNG units at all because nothing of value is lost. No 10% net gain might be applied because 10% of zero is zero. However, there is also some government discussion about whether a set amount of net gain will be needed even under these circumstances.

1.3.2 “Low” distinctiveness

1.3.2.1 These are common land uses which the Government thinks have relatively little, but still some, value to wildlife. They usually represent land that is closely managed for the benefit of people living and working on it but also harbours some wildlife as an indirect result of this use. The most common are arable cropland, “improved” grassland (i.e. productive grassland that is frequently ploughed up, fertilised and/or reseeded), commercial timber plantations and residential gardens.

1.3.2.2 In practice, farmers are unlikely to produce many of these units. Almost all agricultural land will be low distinctiveness at a minimum. Therefore, there is simply not much scope for producing more of this kind of land for biodiversity, because most of the country is already at this distinctiveness or higher. The only way to create units of this habitat type would be something along the lines of taking up a hardstanding area and putting it back into cropping or intensive pasture.

1.3.2.3 When lost to a development, a low distinctiveness habitat must be compensated, but any other low distinctiveness or higher habitat will do, regardless of what kind. Any higher distinctiveness habitat can also be used, and this will quickly be worth more units than what was lost as lower distinctiveness habitats are worth fewer credits.

1.3.2.4 For example, if a developer wanted a residential development on an arable field (low distinctiveness), they may be able to make up a significant proportion of lost habitat just through the gardens of the houses in the new development. The remainder, plus the 10% net gain, might come, for example, from paying a livestock farmer to reduce their inputs on a few fields, turning these fields from improved to unimproved pasture. Because the unimproved pasture is a medium distinctiveness habitat, relatively little of this will be needed to make up for the loss of a larger area of arable cropland.

1.3.3 “Medium” distinctiveness

1.3.3.1 These are relatively common habitats which are frequently easier to establish than the higher tiers, while still being very important to the nation’s wildlife. They are enormously varied, covering some unusual land uses such as coastal silt and “green rooves” in cities. Some of the medium-distinctiveness habitats farmers are most likely to come across include “Stewardship-style” areas on arable land such as buffer strips and wildflower margins, “unimproved” pasture (i.e. not fertilised, ploughed or reseeded) that does not contain any particular rare plant life, most wildlife ponds, and many areas of planted amenity woodland.

1.3.3.2 Turning low distinctiveness land into habitats of this tier is likely to be the most common way for farmers to earn BNG credits. Those who have already been part of a Stewardship scheme will be familiar with many of the habitats which can be used, and actions such as digging a pond or committing to minimise inputs on grassland can, with adequate planning, fit into a commercial farming operation.

1.3.3.3 Broad types – Medium distinctiveness habitats are split up into several broad types. These include grassland, heathland, woodland, arable, inland water, coastal, urban and “sparsely vegetated” land. When medium distinctiveness land is lost to a development, it must be replaced with either other medium-distinctiveness habitats of the same broad type, or any habitats of “high” or “very high” distinctiveness.

1.3.3.4 This means that if the residential development mentioned above included building on what is currently a wild bird seed mix, the developer would need to offset this by paying for either other medium-distinctiveness arable habitat or any high or very-high tier habitat to be created or improved. This means the developer could use units from a new buffer strip or wildflower margin, but they could not use units from someone reducing fertiliser inputs to create semi-natural grassland, because this is a different broad type of habitat in the same tier. They could, however, pay for creation or improvement of a traditional hay meadow, because although this is of a different broad habitat type it is also a very high distinctiveness habitat. They could also not use units from someone turning a disused car park into productive cropland, even though this is the same broad type of habitat, because the resultant cropland would be of lower distinctiveness than the lost seed mix. In essence, a lower tier of the pyramid can never compensate a higher one.

1.3.4 “High” distinctiveness

1.3.4.1 These are rarer and very valuable habitats which are generally difficult to replace if they are lost. Although varied, there are actually relatively few of these kinds of habitats affecting farmland, not least because no arable habitats are considered any higher than medium distinctiveness. Perhaps the most significant are various types of relatively rarer woodland, for example lowland deciduous and native pine. Others to note include upland calcareous grassland and “tall grassland herb communities”, most open heathland, wetland reed beds and many inland water features including reservoirs, lakes and more ecologically important wildlife ponds.

1.3.4.2 Most of these habitats are difficult for farmers to create, with the two grassland habitats in particular unlikely to be feasible in most circumstances (some very high distinctiveness grassland habitats are likely to be easier to establish). However, those engaging in woodland planting could aim for a woodland from this tier, and an ecologically important wildlife pond is something a farmer in a priority location could potentially create. A heathland farmer could likewise create open heathland by sympathetic scrub clearance.

1.3.4.3 Replace with exact same habitat – Where a developer is building on a high distinctiveness habitat, they must replace it with the exact same habitat elsewhere. In other words, if they have somehow gained permission to fill in a high-priority wildlife pond as part of their development, they must ensure another such pond is created (or improved) elsewhere before they can proceed. It may be that for some habitats in this tier, very few credits are available as few farmers can create these habitats, so the credits could be very valuable indeed to a developer requiring them. However, biodiversity offset is in addition to, rather than in replacement of, other planning constraints. Developers may find it difficult to receive permission to build on them before BNG is even considered, especially as many of these kinds of habitats will be found on protected sites such as National Parks, nature reserves and SSSIs. They are also largely quite rare, meaning there are relatively few of them to develop on in the first place. Therefore, whilst supply of credits may be limited, demand may be limited even more. However, where a farmer can create a high- rather than medium-distinctiveness habitat, other factors such as cost being equal, they still should consider this. Even if they cannot find a buyer for that exact habitat, the higher distinctiveness means they should have more credits to sell to buyers wanting medium-distinctiveness habitats, or lower distinctiveness habitats in general. These credits will also be more versatile because they are not limited to a single broad type of medium-distinctiveness habitat, likely making them more valuable.

1.3.5 “Very High” distinctiveness

1.3.5.1 These represent what are, in theory, the rarest and most valuable habitats in the country. They range from the highly specialised, such as “littoral seagrass on peatland” to the surprisingly familiar “meadows”. The latter category includes traditional hay meadows which can conceivably be created, albeit with some effort, by a livestock farmer moving to a less extensive operation. “Wood pasture and parkland” and “traditional orchards” are also both included and are relevant to many traditional estates as well as farmers experimenting with agroforestry. Other habitats in this tier which might be found on-farm include lowland dry acid grass, purple moor grass (known in Devon as “Culm grass”) and all kinds of peatland.

1.3.5.2 Under the new rules, developers will require special permission from the Secretary of State before they can build on these kinds of habitats, which will require a specially tailored compensation strategy. This is, we think, likely to be prohibitive even to the largest private developers. However, it may arise in relation to some national infrastructure projects. This means the market for these units is likely to be very small, but they will be extremely valuable to those that require them. Note that because the tier below this, “high distinctiveness” requires like-for-like replacement, these credits can only be traded down for medium and low-distinctiveness offsetting. However, creation of these habitats has the potential to produce so many units that, once again, it is worth seriously considering creating these where possible compared with other tiers.

1.4 SUMMARY

1.4.1 The meaning of all this is that we now have some understanding of how the national BNG market will work in practice and that some expertise will be needed to operate efficiently in it.

1.4.2 Developer demand for low distinctiveness (LD) credits will represent a floor price. We think most credits farmers create will be medium distinctiveness (MD) of one kind or other. When there is no demand in their area for the specific type of MD credit a farmer has created, they can sell their credits on the LD market instead to receive some profit. If there was more demand than supply for all types of MD credit, the LD price will tend to match whichever MD credit is the least expensive.

1.4.3 MD credits will, for their part, have their markets split by type. The most commonly produced, and most in demand, will be medium distinctiveness grassland (MDG) and medium distinctiveness arable (MDA). This is because farmers will find these kinds of credits easiest to produce, and also because developers are most likely to develop this kind of land. However, there will also be markets for medium distinctiveness heathland (MDH) in the parts of the country where it is relevant, medium distinctiveness water (MDWa) where a pond must be filled in for a development, and medium distinctiveness woodland (MDWo) mostly for infrastructure projects because planning permission for housing or commercial use is rarely granted on established woodland. Urban, intertidal and “sparsely vegetated” land will also each have their own MD markets. These will be more specialised, so relevant to fewer farmers, but those who do farm along coastlines and river estuaries, or in areas with exposed rock, would perhaps do well to take note.

1.4.4 High distinctiveness (HD) and very high distinctiveness (VHD) will contain within them a “micromarket” for each specific habitat, with both buyers and sellers sometimes waiting for long periods before being able to do high value trades. We think they will behave in a similar way to the water abstraction licence market, in this sense. However, we also expect that sellers in the top two tiers will frequently prefer to save themselves the time and complexity and sell their credits on the LD or the MD market instead. This may mean very rich rewards for those who wait!

1.4.5 Therefore this illustrates why the marketing of BNG units should always be carried out nationally as distinctiveness can make units in one LPA that much more valuable than in another even having taken into account the reduced number that can be sold.

1.5 BNG TRADING

1.5.1 DEFRA initially proposed figures from £9,000 to £12,000 then £20,000 to £25,000 per biodiversity unit but each agreement will have its own value. Whilst it is not yet a mandatory requirement, many Local Planning Authorities already require some form of biodiversity gain. Demand will only increase in 2023 with DEFRA estimating 6,000 acres per year required once the market is fully developed.

1.5.2 We have marketed our first lots of BNG units in 2022 as some planning authorities already required a net gain as part of a planning application. We have seen prices range from £15,000 to £35,000 per unit. Sales have been arranged beyond the same LPA confirming there is a national marketplace for BNG units. However, the market is sporadic and still very much emerging. The best illustration of how the 2023 market could behave when BNG becomes a statutory requirement for all developments comes from a sale of one unit needed at speed by a central London developer who ended up paying £90,000. It is expected demand will surge leading up to the proposed deadline in November and until the statutory market settles in prices are likely to be volatile.

1.5.3 Farmers who have BNG units to sell, i.e. who have completed a Biodiversity Metric calculation should contact us about our BNG register and how we can market these units on their behalf. We are preparing for the first national sale by tender of multiple lots of units and are inviting entries. If you have yet to complete a Biodiversity Metric calculation and are interested in using parts of your holding to improve biodiversity, you should contact us to ask about a free farmer’s desktop assessment to find out your land’s potential and make best use of this opportunity.

1.5.4 Letting land to environmental investors in 2022 continued in earnest but it has become clear some agreements, whilst seemingly guaranteeing to pay healthy rentals for 30 years, could end up with over 70% of the profit of creating and selling the BNG units going to the investor. We have seen more and more clients having worked through the figures coming to us deciding to carry out such BNG projects themselves keeping at least 95% of the profit by using our services (managing/advising on the projects from conception to completion of sales) after only a proportionally small outlay for BNG metric surveys before a sale.

1.6 FURTHER OPPORTUNITIES FOR FARMERS AND LANDOWNERS

One of the most interesting aspects of the Government’s approach to farming and environmental policy is their view on the ‘stacking’ of benefits. Land may not be restricted to one scheme as long as the actions paid for are producing differing outcomes. Land that has been entered into a Biodiversity Net Gain agreement for example may also be used to create saleable carbon credits if woodland were planted as part of it. DEFRA hope sections of the Environmental Land Management Scheme will be taken up by the majority of farmers providing payments for certain beneficial farming practices and landscape management. There is the potential to combine these agreements with payment for nitrate and phosphate offsetting, carbon sequestration and BNG.

2. CARBON

WOODLAND/PEATLAND/SOIL CARBON TRADING OVERVIEW

2.1 Since opening our carbon trading desk there has been a lot of interest from parties looking to both buy and produce carbon credits. Our trading registers have expanded and now specialise as Woodland, Peatland or Soil carbon credits.

2.2 In the UK, we have the Woodland Carbon Code and the Peatland Code with a Soil Carbon Code being worked upon. These set Government approved standards for UK woodland creation and peatland restoration projects, which the landowner can use to verify and then trade the carbon they sequester in the woodland or peatland. This creates security for the purchaser who knows the carbon credit has been professionally validated with sequestered carbon having ‘permanence’ and providing ‘additionality’ to what would have been sequestered anyway.

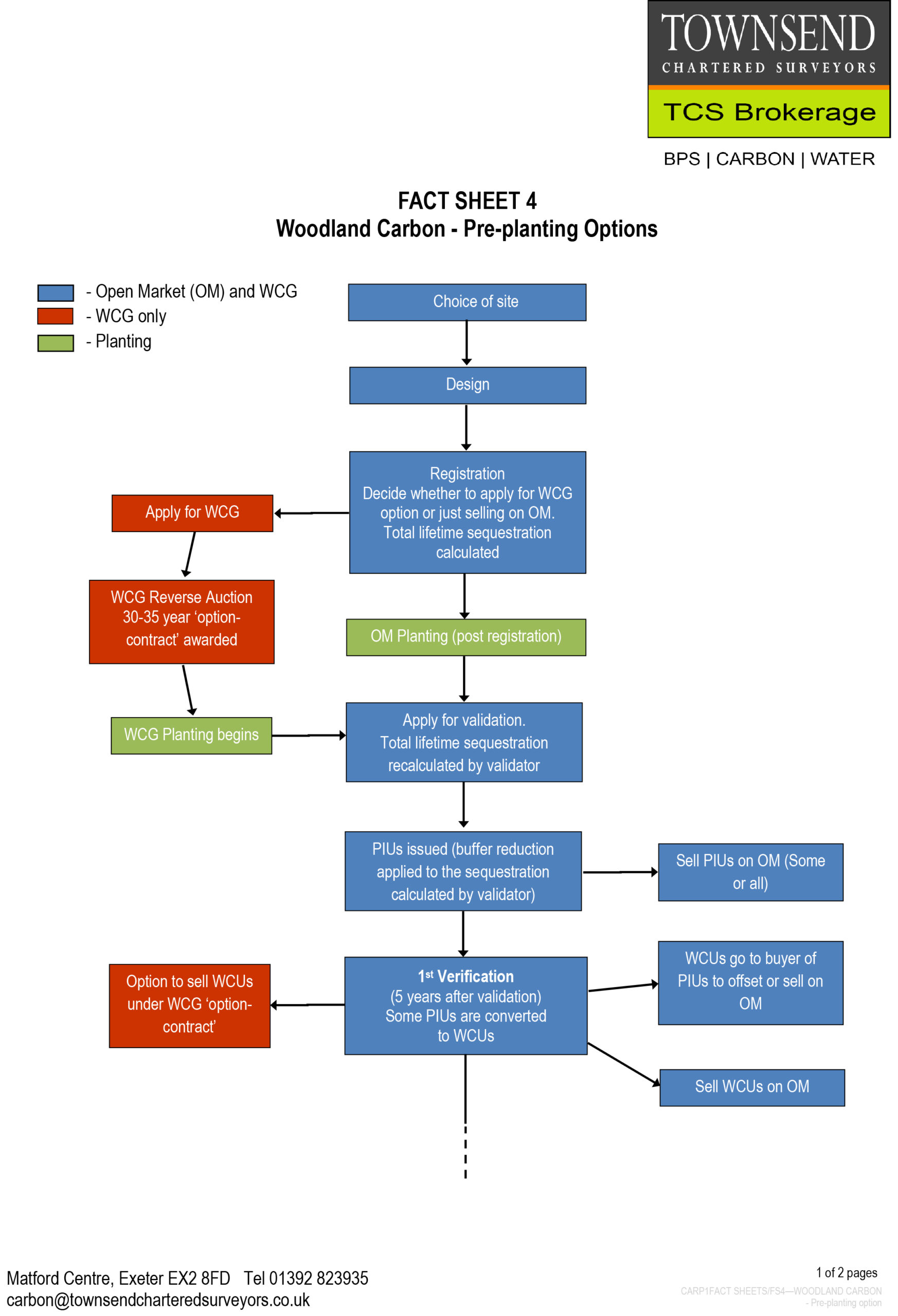

2.3 The Woodland Carbon Guarantee is a scheme that uses the Woodland Carbon Code. This provides the landowner with a confidence that their captured carbon can be sold at a guaranteed minimum price via a contract with the Government or sold in the open market, whichever provides the best value. The option to sell to the Government via the WCG saw our clients having accepted their offer prices of £22.50/unit in the November 2022’s reverse auction

2.4 Also one of the most attractive elements of creating new woodland is that BPS payments for 2023 can continue in these areas when using the various grants available (including Countryside Stewardship Woodland Creation and Woodland Carbon Fund capital grant), provided the land was claimed on for Single Farm Payment in 2008.

2.5 If you are interested in woodland creation and the selling of carbon credits or wish to purchase some to offset your business’s carbon footprint then contact our carbon trading team.

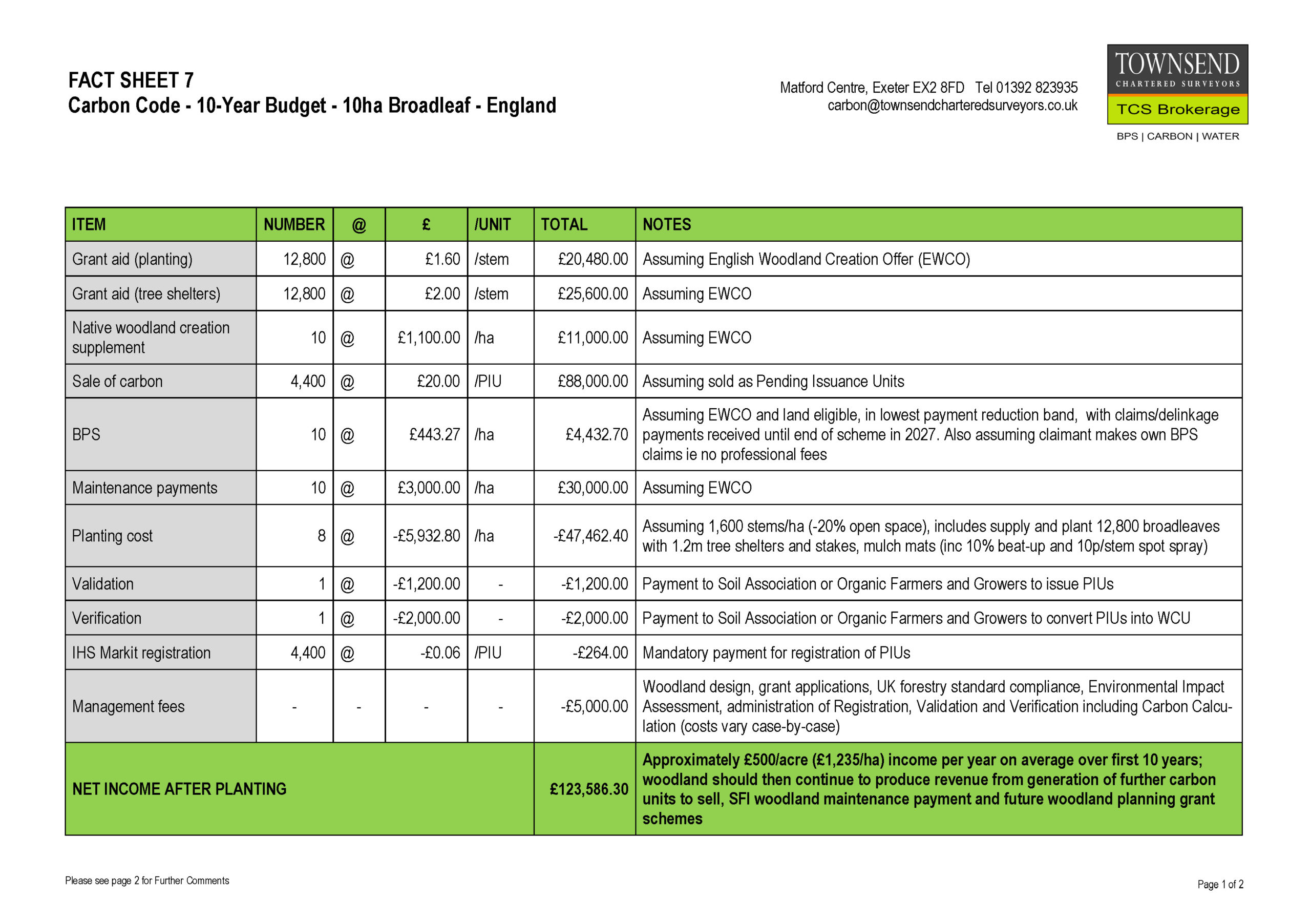

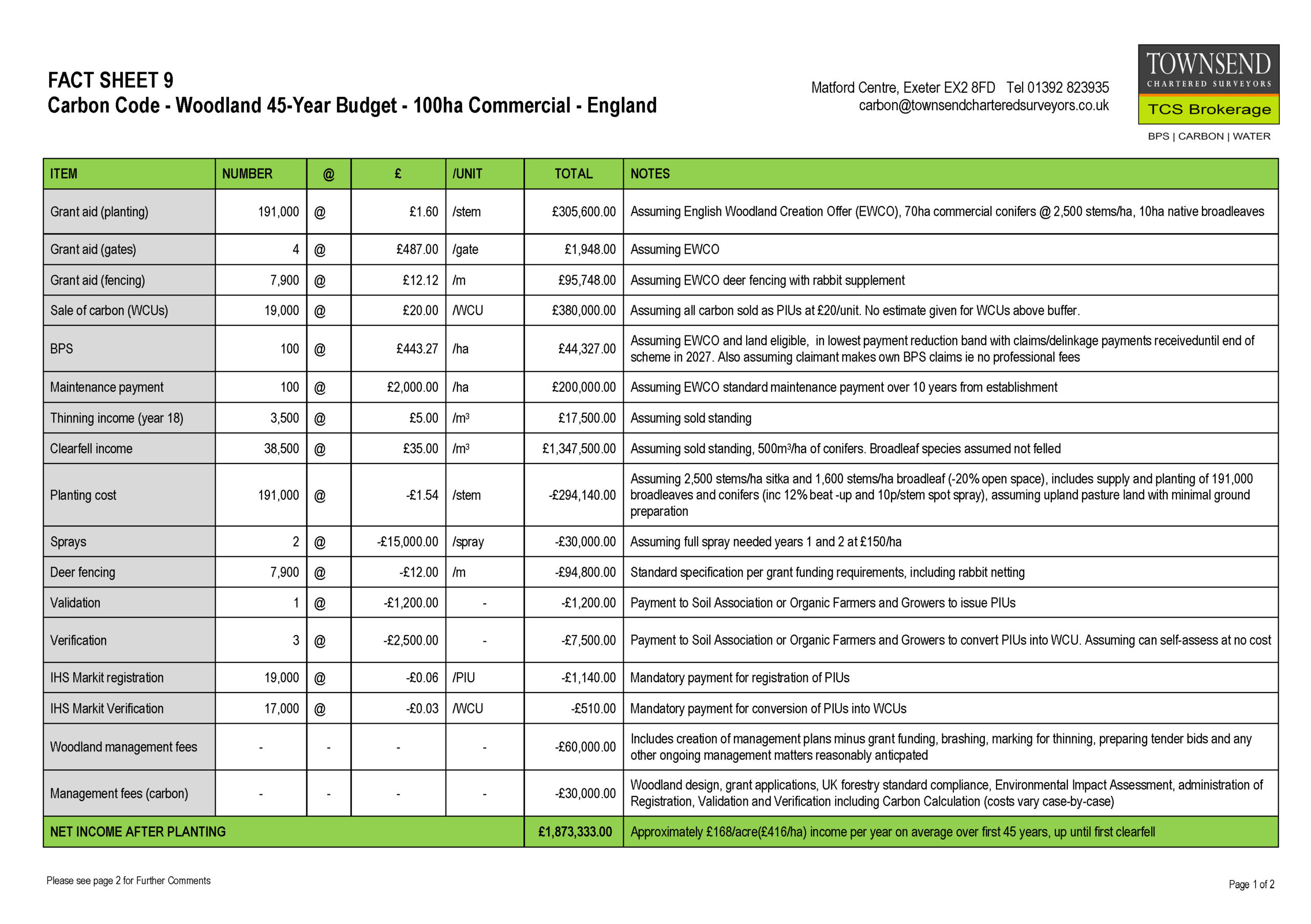

2.6 We currently have 13,497 Pending Issuance Units available for sale with more at various stages of development coming to the market soon. We are registered project managers with the UK Land Carbon Registry and are a “one-stop shop”, with our own foresters and ecologists covering the whole of the UK. We will help you choose the best site (including acquiring land if you do not already have a site), design the woodland with you ensuring the most carbon can be sequestered using the Woodland Carbon Code calculator from the outset, registering the woodland, ensuring you consider, in England, making an application to the Woodland Carbon Guarantee reverse auction, and that you meet the deadlines for validation and verification and get the most from current woodland grants. We can also manage the actual planting and ongoing management. Woodland Carbon Units in 2022 have been fetching £25-30/unit with £12-20/unit for Pending Issuance Units. We can ensure you make the most also of BNG on any a new woodland planting and from other latent Natural Capital assets.

2.7 The Peatland Code involves improving peatland in poor condition. This peatland will release carbon stored into the atmosphere until it is improved. It is this improvement that generates credits. The Code measures peatland carbon based on how much would have been released without the improvement. The improvement would involve actions such as rewetting dry areas and re-establishing permanent green cover over bare patches. Activities can range from simply blocking drains and changing grazing regimes to full scale “rewilding” projects.

2.8 We have clients looking to acquire peatland for restoration projects, contact us if you have suitable land.

2.9 We currently have a register of Soil Carbon Units to sell from individual farms. These types of unit are not currently part of a verified scheme but can still be used for voluntary offsets. They are a product of intensive soil management and crop rotations. Farmers can capture carbon through soil management and changing of farming practices. A Government Soil Carbon Code is under development, register with us now to make the most of the opportunities it will present once complete.

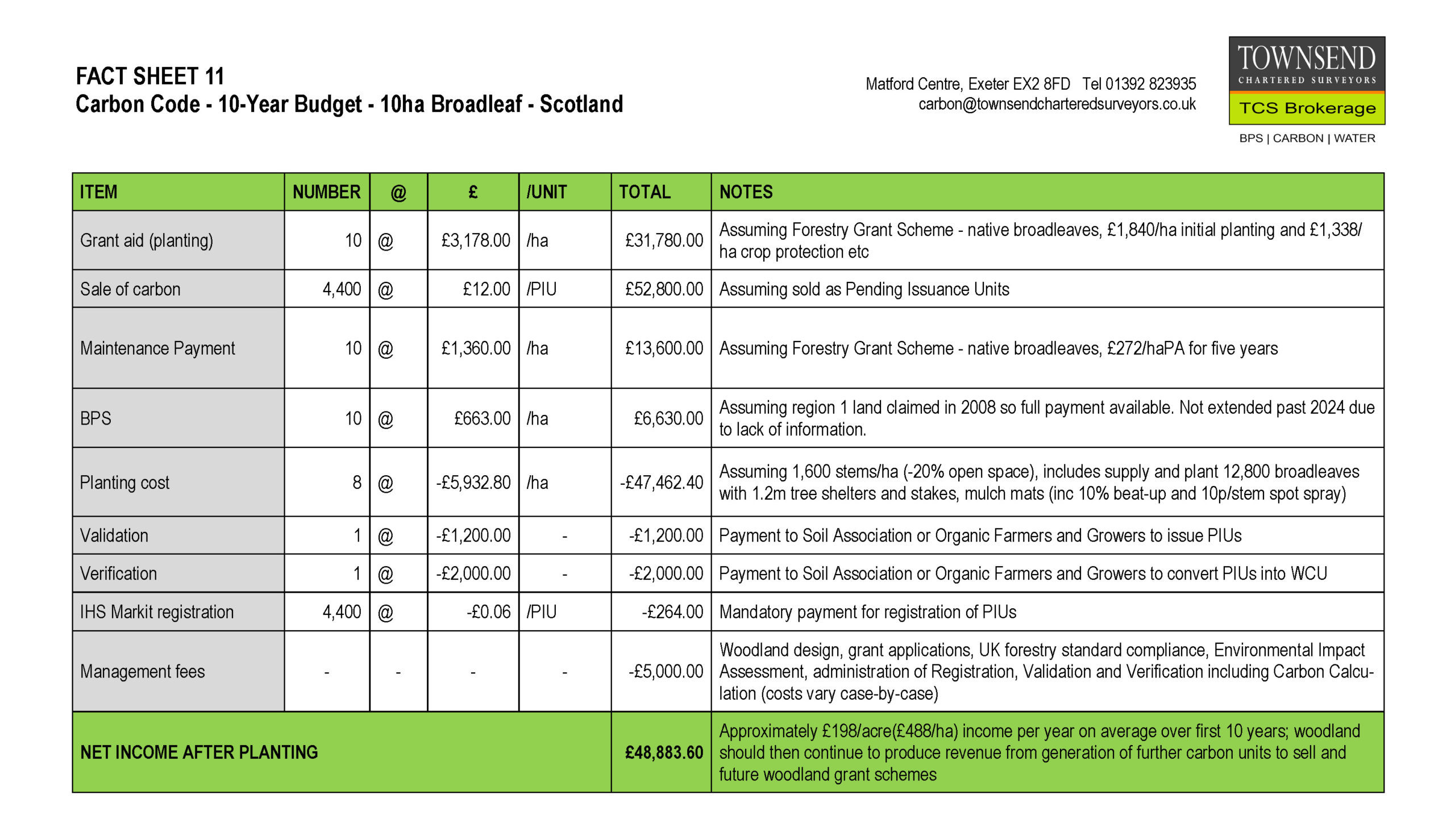

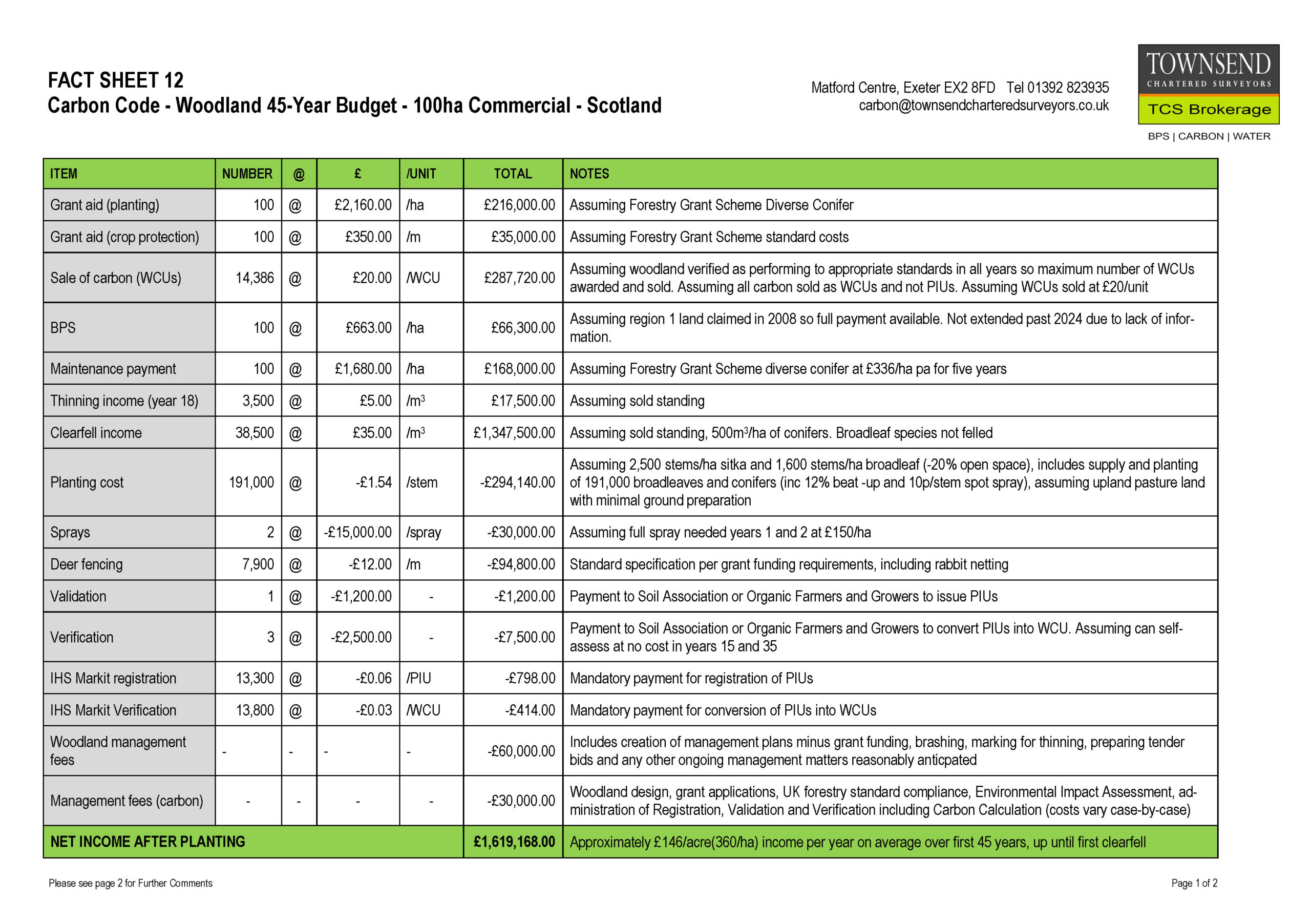

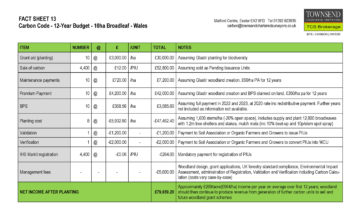

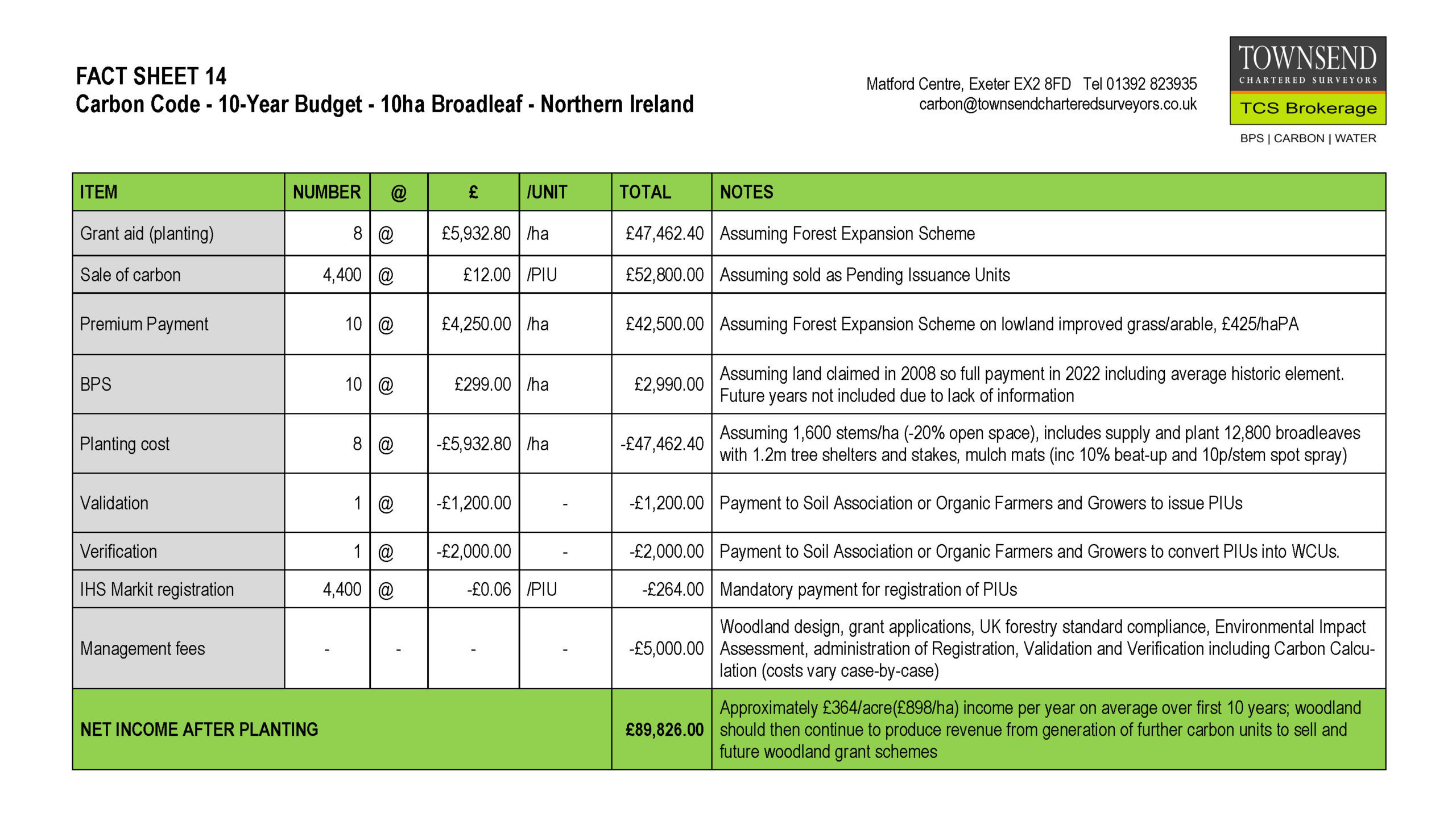

2.10 Woodland Carbon Fact Sheets

|

|

|

|

| Fact sheet 4 – Pre-planting options | Fact Sheet 6 – Guidance notes | Fact Sheet 7 – Carbon code – 10-year budget – 10ha broadleaf – England | Fact Sheet 9 – Carbon code – 45-year budget – 100ha commercial – England |

|

|

|

|

| Fact Sheet 11 – Carbon code – 10-year budget – 10ha broadleaf – Scotland | Fact Sheet 12 – Carbon code – 45-year budget – 100ha commercial – Scotland | Fact Sheet 13 – Carbon code – 12-year budget – 10ha broadleaf – Wales | Fact Sheet 11 – Carbon code – 10-year budget – 10ha broadleaf – Northern Ireland |

3. NITRATES & PHOSPHATES

3.1 Nitrate offsets involve developers buying ‘nitrogen credits’ – to offset the nutrient footprint of new homes by contributing to mitigation schemes. This secures agricultural land, taking it out of intensive farming thereby reducing nitrogen inputs. This could include the creation of habitat such as wetlands, meadows and woodland. The Government had been trialling a pilot scheme on the Solent in Hampshire where development had previously been prevented because of nitrate pollution to the River Solent.

3.2 Natural England issued new nutrient neutrality guidance to Local Planning Authorities in March 2022 stating they can only approve a proposal for development if they are certain that it will have no negative effect on a ‘protected site’. The total LPAs affected have now been brought up to 74 including the further 42 added in 2022. The guidance also includes a new generic nutrient neutrality methodology, catchment specific calculators and an updated catchment map. Various mitigation schemes have been implemented, run by a range of landowners from farms and estates to Eastleigh Borough Council and the Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust. Whilst being able to enter land into these schemes is very much location dependent, there is much competition among developers for these ‘credits’ and if land is suitable, it may well be worth looking at. Professional advice should be sought before trying to calculate your land’s potential as specialist knowledge is required.

3.3 Developers will bid to use these improvements to offset nitrate contamination from their developments. Landowners listing improvements will receive a payment from the highest bidding developer to put them into place. The developer can then use them to help attain planning permission.

3.4 Although the current nitrate pilot scheme is limited to one particular area, the Government has suggested it may be expanded into other areas facing similar issues which we have already seen in 2022. Nutrient Budget Calculators have been produced and are in place for planning in areas such as the Test Valley Borough Council.

3.5 In the Somerset levels and Moors, there is a need for protection from further phosphate pollution. This restricts the building of new housing and other developments in the area as, before determining a planning application that may increase phosphates within the catchment, local authorities must undertake a Habitats Regulations Assessment (HRA). Some County Councils with affected catchment areas provide a Phosphate Budget Calculator for developers. As part of the planning application process, developers will work out their site’s pollution levels, then consider a range of measures such as removal at source, mitigation, and if necessary, offsetting of phosphate. Offsite offsets will include agricultural management in catchment-based areas, offsetting schemes/accredited projects, nature-based efforts such as habitat creation and improvements to water recycling. Change of land use for mitigation includes constructing wetland, woodland, heathland and meadow among others. Interestingly Somerset County Council suggest any phosphate schemes may include dual-use mitigation schemes taken from the Environment Act 2021 such as projects used for the 10% BNG requirement.

3.6 In Somerset as with other LPAs using offsets to allow development is very much a work in progress and some LPAs are scampering around trying to quickly ease up the backlog of planning applications held up by phosphate issues including going to the extreme of buying offset rights to sell to developers, a practice already seen with LPAs trying to tackle their own voluntary approach to BNG and which is unlikely in our opinion to be able to continue.

3.7 Register your interest with us now to take advantage of the opportunities as these markets spread.

4. BPS ENTITLEMENTS

4.1 2022 ENGLISH BPS ENTITLEMENTS OVERVIEW

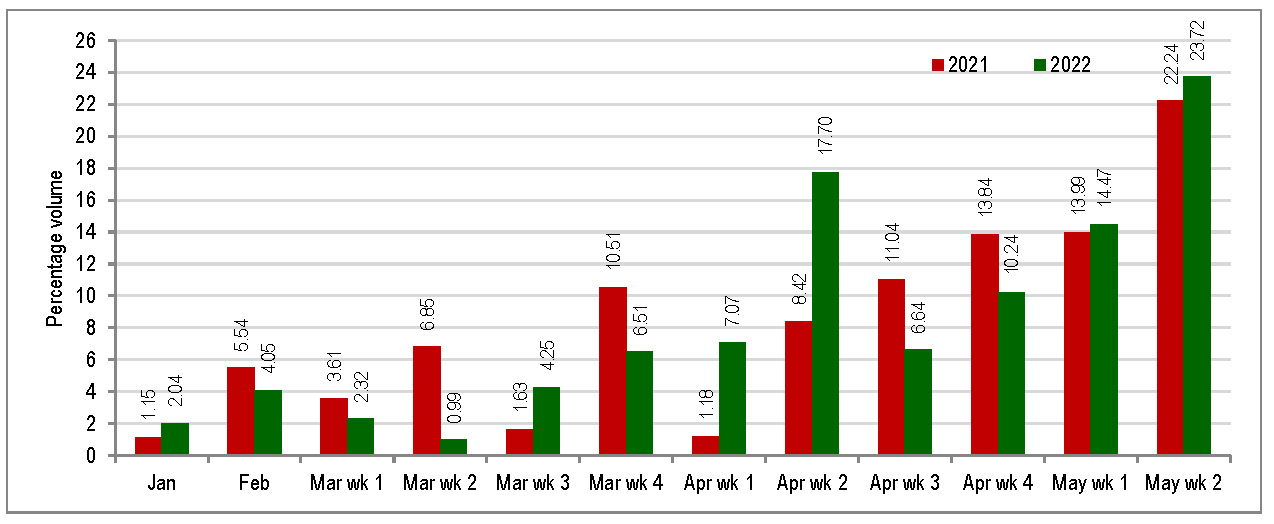

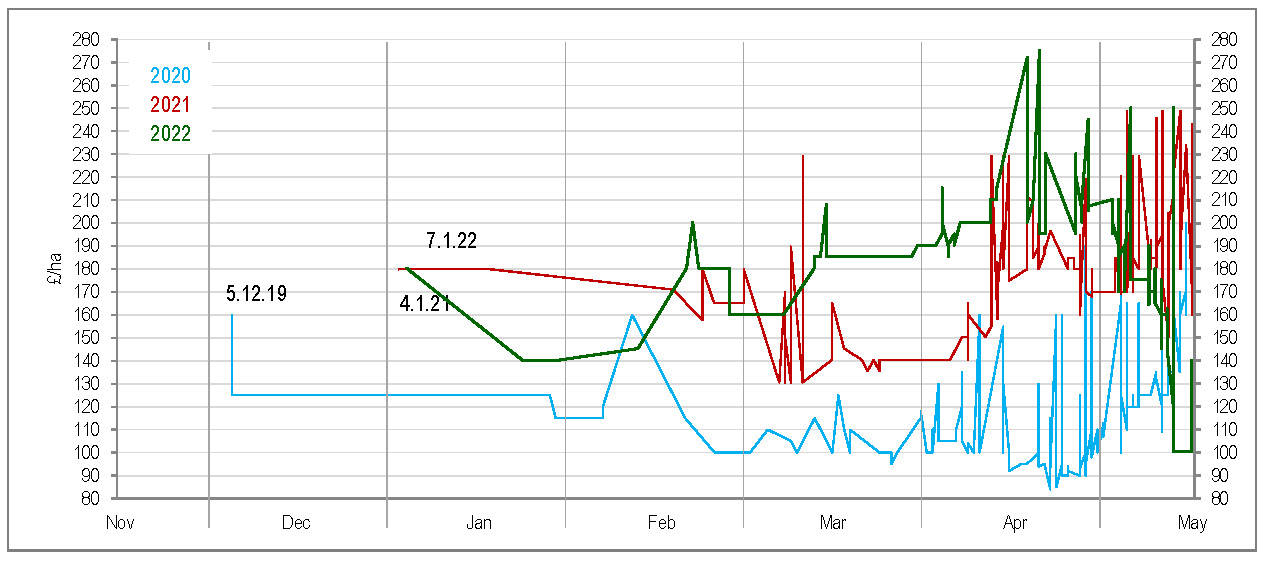

4.1.1 When the 2022 market opened, prices were expected to be lower than previous years, reflecting the phasing out of BPS. DEFRA had confirmed that 2022 and 2023 would be the last years that a BPS application would be required and, following on from 2021, entitlement payment values would receive further increasing reductions based on a claimant’s total claim size. This figure meant the smallest farmers of under 128ha would receive £186.57/unit whilst those with over 642ha would receive £139.93/unit for any new unit purchased. On this basis early trading was expected to be both slower and lower than last year’s average.

4.1.2 In February, DEFRA announced how delinkage and the lump sum exit support scheme would be implemented. From 2024 all entitlements will be removed as a component of the Basic Payment Scheme, the remaining payments up to 2027 will be made regardless of land held or farming activity taken. The amount received would be based on a reference period; the average claim value in 2020, 2021 and 2022. As the reference period included this claim year this led to a surge in demand, the announcement focussed minds on maximising the total claim on any eligible land as it would in effect contribute an extra third of an entitlement to the delinkage sum received before any reductions.

4.1.3 The lump sum exit support scheme had a dramatic effect on demand and value. Further information meant that this was worth 2.35 times the average claim between 2019, 2020 and 2021 with a maximum of £99,875. A key point clarified was that the claimant had to surrender enough entitlements to cover the equivalent of their 2021 claim or receive proportional reductions in the amount received. This had the unintended consequence of those who wished to take part having to purchase large amounts of entitlements to replace those lost in situations where they had to return entitlements to a landlord when giving up land or when it had been agreed that the entitlements would be transferred as part of a sale of land. As each entitlement surrendered through the lump sum had a value of £547.55/unit, it made sense to purchase enough to meet their maximum total. This had the unintended consequence of driving prices up as retirees wanted to guarantee the most they could and were willing to pay above the market price.

4.1.4 In the weeks following this announcement we saw huge demand from purchasers with relatively low numbers of vendors. Competition kept prices for large lots in the £200-215 bracket with lots of under 5 units fetching as much as £275/unit plus VAT.

4.1.5 Whilst this was initially fuelled by retirees, prices held at this value until the final week when an influx of vendors settled the market. As purchasers were sorted, vendors were left with unsold lots and the price crashed in the final few days as vendors had to sell or be left relying on selling at a far lower price next year.

4.1.6 Due to the Basic Payment Scheme being phased out, 2023 will be the final year of both trading and putting in BPS applications in England. With replacement schemes offering less funding than BPS, farmers must now start looking to other income streams whether through the sale of sequestered carbon BNG units or other ‘natural capital’ assets.

4.1.7 How our graphs are prepared

As before, we are publishing raw data graphs illustrating in detail how the different regional Entitlement markets behaved during the 2022 trading period, which for England ended on the 16th May 2022. Because we use only raw data, there have been no adjustments such as averaging prices for a week or a day, rounding up or down, and any contributions towards the vendor’s sale costs made by purchasers of small lots on top of the purchase price per entitlement are excluded. These graphs show the results of each individual transaction.

4.1.8 General market factors in 2022 trading period

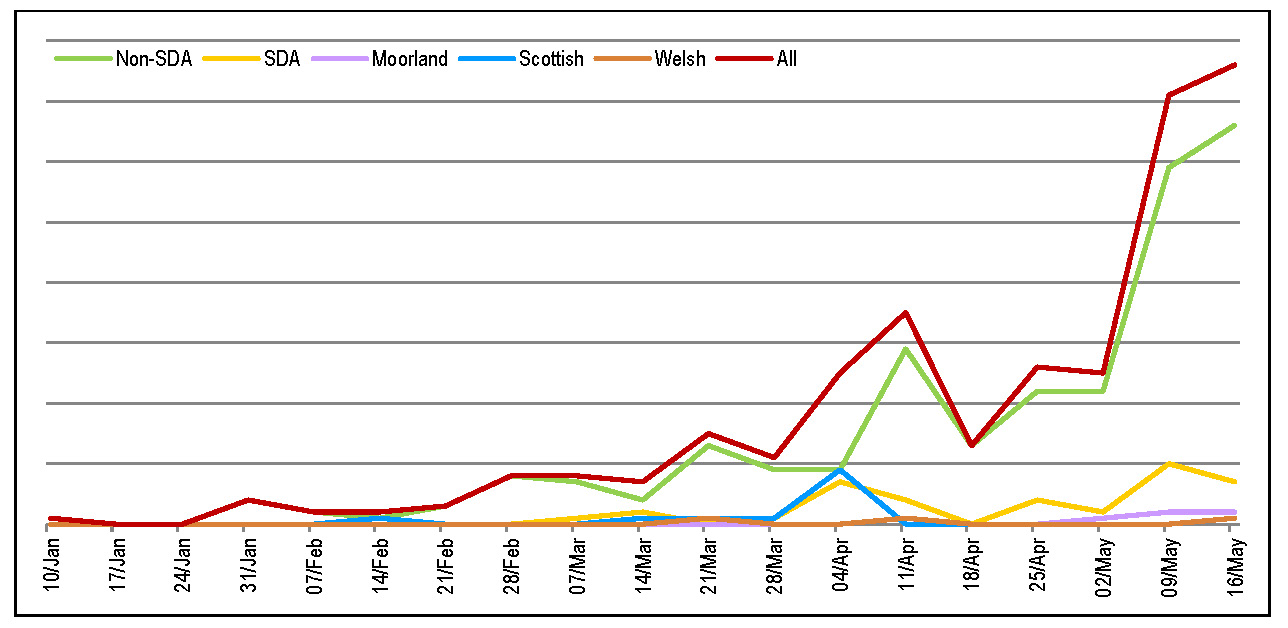

- In 2022 the online entitlement transfer screen went live at the end of January.

- In 2022 the BPS online claim forms were available from the 15th

- Although many agents/buyers made contact in early 2022 most sales were conducted in the last three weeks before the deadline. This may be simply due to many agents not being able to confirm their client’s shortfalls until the last minute, and also purchasers waiting and hoping for prices to dip as the deadline approached.

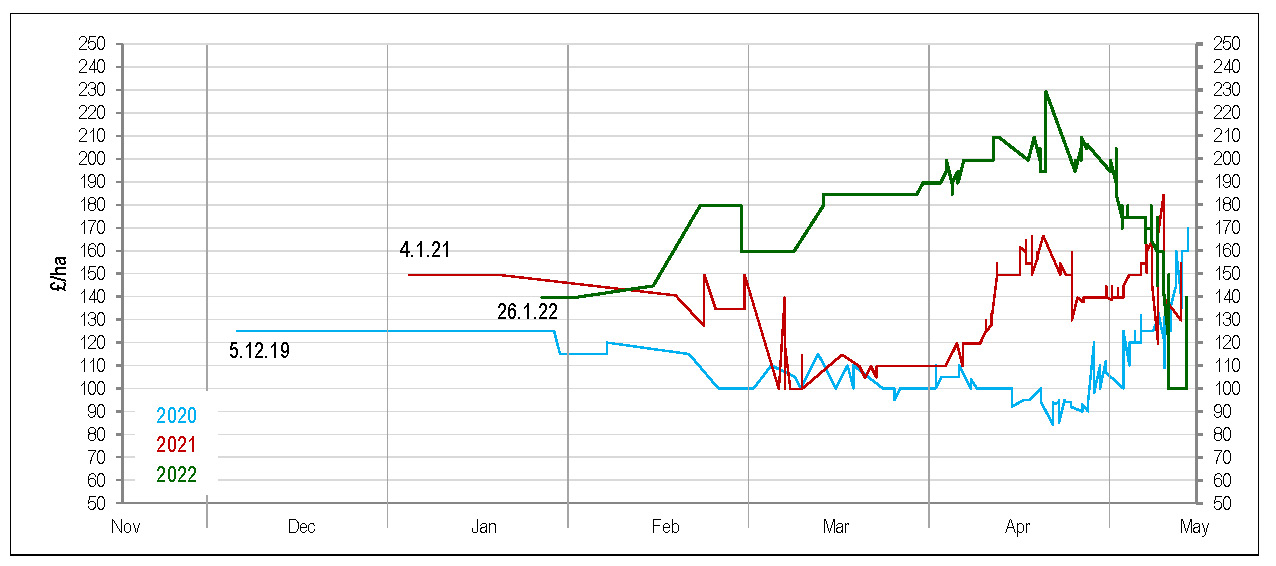

4.2 ENGLISH NON-SDA – VAT REGISTERED

4.2.1 The season started with many tentative enquiries for various lot sizes. It was clear there would be significant interest in trading but both vendors and purchasers were cautious, needing to decide what prices they considered acceptable with an uncertain outlook. The first sales were agreed in early January starting at £140 plus VAT (less than the average price of £150 for entitlements sold in 2021). Small lots of under 3 started at £180/unit plus VAT. Non-VAT lots fetched £150/unit.

4.2.2 These prices were consistent until late February. Then, after the market had had time to digest news of the workings of the lump sum and delinkage, the first purchaser seeking a large lot for lump sum purposes completed at £180/unit plus VAT. Small lots were fetching £200/unit plus VAT.

4.2.3 In early March, prices fell to £160/unit plus VAT for a series of mid-size lots and it looked as if demand from retirees would not be that high after all.

4.2.4 However, this would not be the case, as during the rest of March, more came forward, large lots were fetching £185 plus VAT, and vendors who had already sold at this price now expected this figure for all their units and more.

4.2.5 By the last day of March and into early April prices hit £190/unit which quickly turned to £195 plus VAT.

4.2.6 By the 4th April a milestone was reached, with large lots breaking the £200/unit plus VAT barrier, a figure usually reserved for small lots. The price then fluctuated between £190 and £215/unit plus VAT.

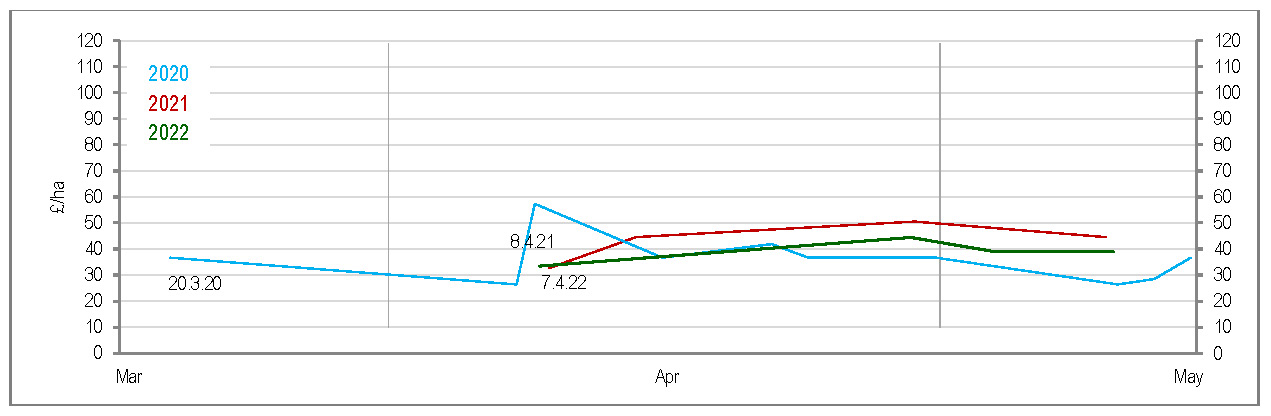

Graph A – Non-SDA registered sale of >10ha

Graph B – Percentage volume of all Non-SDA sales in months and weeks

4.2.7 The unusual nature of this year’s market was exemplified by the fact between 8th and 21st April almost every sale was completed at over £200/unit plus VAT with many at £205-210/unit plus VAT. Very small lots hit £272/unit plus VAT.

4.2.8 After the 21st April all were still at or over £195 plus VAT and it was only by the 4th May that the price fell to £190/unit plus VAT.

4.2.9 It was at this point that the market started to falter, throughout the 5th May sales concluded at £185, £175 then £170 plus VAT. Up to the 10th May prices hovered between £160 and £180 plus VAT.

4.2.10 The final week of trading saw lots of activity in the first few days, from £165 slipping to £120/unit plus VAT. The last few days of trading saw the price crash to £100/unit plus VAT as demand dried up and lots remained unsold. Whilst some mischievous speculators put in bids of £25/unit, vendors sensibly rejected this and were prepared to await the final year of BPS trading in England in 2023.

4.2.11 The average price for the season was £180 plus VAT, up from £151/unit plus VAT in 2021.This represents a six-year high and the second highest average since direct subsidy became the Basic Payment Scheme in 2015.

Graph C – 2022 Weekly flow of trade

4.2.12 Demand for small lots

- There was demand for a variety of lot sizes, small lots being shown in the graph below.

- As always, they tend to fetch a higher price per unit than large lots with the value reflecting the amount paid for larger lots.

- With high prices for large lots, the small lot price went over £270/unit plus VAT on several occasions, the delinkage aspect on anything claimed this year making this figure still worth the initial outlay.

Graph D – Non-SDA VAT registered sales of <10ha

Graph E – Non-SDA VAT registered sales – all lot sizes

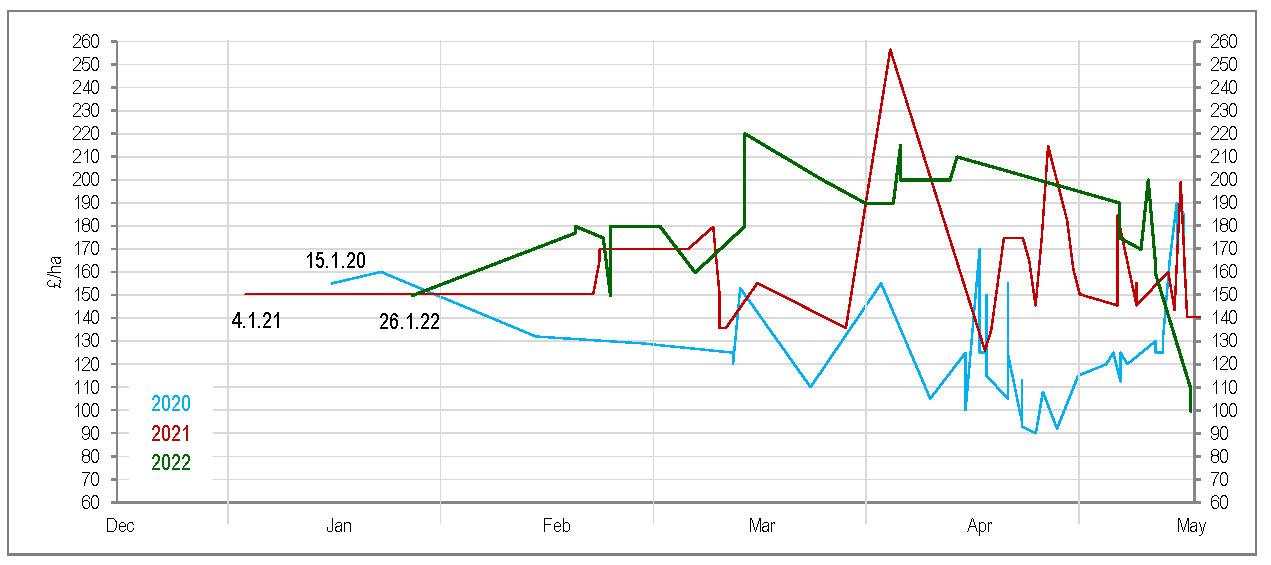

4.3 ENGLISH NON-SDA (Non-VAT Registered)

4.3.1 There was demand for non-VAT lots, as always, however the high prices reached across the board quickly made the usual non-VAT premium inconsequential.

4.3.2 Whilst non-VAT purchasers and vendors were matched where possible there were no real significant differences in prices achieved for most of the season.

Graph F – Non-SDA Non-VAT sales – all lot sizes

Graph G – Non-SDA non-VAT registered sales <10ha Graph H – Non-SDA non-VAT registered sales >10ha

4.4 NON-SDA NAKED ACRE LETTING

4.4.1 It is perhaps surprising that after the announcement that this year’s BPS claim would contribute to the delinkage payment, there was not more demand for naked acres. Compared to last year there were far fewer potential tenants, however this in turn was reflected in the lack of landlords. Prices per acre were lower than previous years which made it less attractive to landlords.

4.4.2 Naked acre lettings were agreed in April at £60/acre and May at £65 per acre.

4.4.3 The high prices vendors could achieve selling entitlements at various points in the season meant potential tenants may have decided to simply sell for a greater initial cash boost, a decision influenced by the expected low price for selling next year.

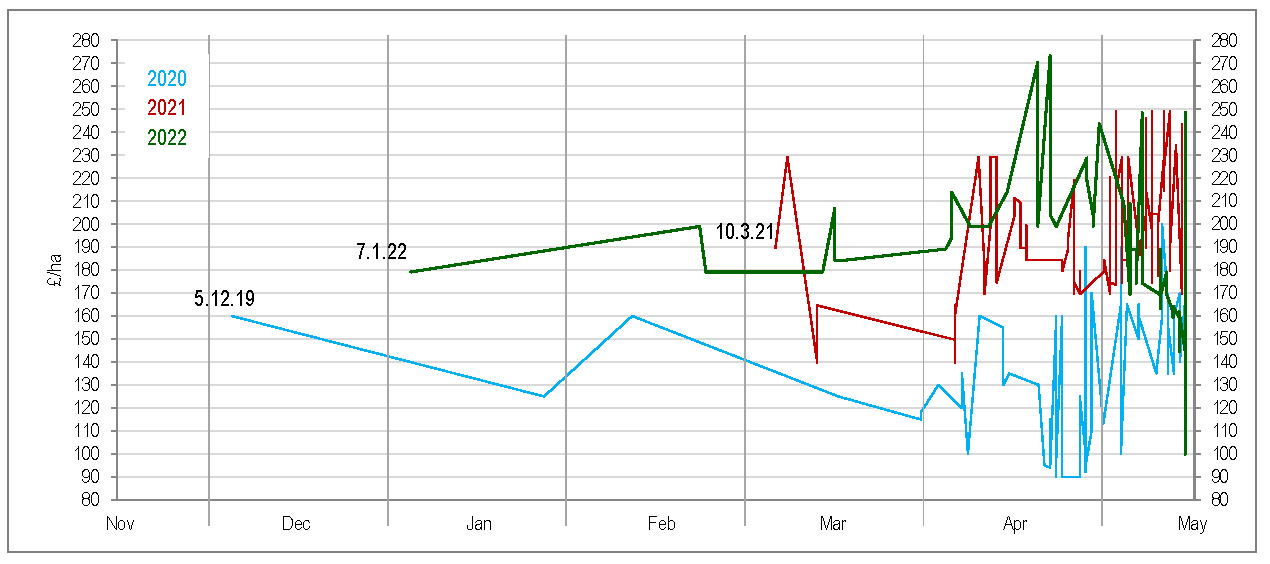

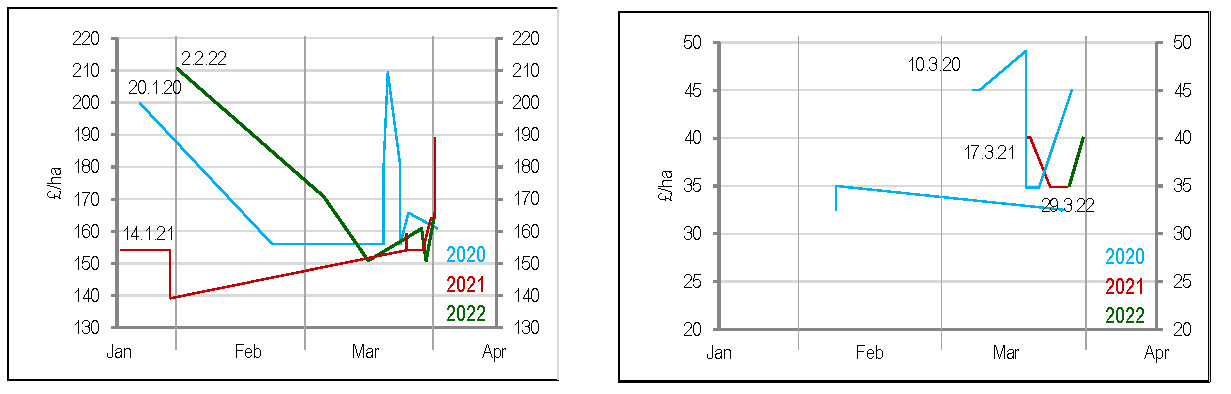

4.5 SDA

4.5.1 The SDA market kicked off later than Non-SDA with the first sales completed in early March. There were initially fewer purchasers than vendors which kept prices relatively low.

4.5.2 The first sales of SDA entitlements were agreed in early March at £170 plus VAT per entitlement, the same point as where the 2021 market started.

4.5.3 Through March this value varied between £150 to £175/unit plus VAT reflecting the low demand and high supply. The exception was small lots which fetched a higher £244/unit.

4.5.4 The start of April saw increased demand with more purchasers and prices for medium-sized lots rose to £180 then £195/unit plus VAT although larger lot sizes were still at £175/unit plus VAT

4.5.5 From early May up until the deadline, there were a series of large purchasers and supply ran very low. Prices returned to £185 before achieving £200/unit plus VAT for a series of non-VAT sales. The final week saw a flurry of last-minute sales completed meaning that the overall quantity sold ended up well above previous years.

4.5.6 Compared to last year the average lot price for 2022 SDA entitlements over the whole of the trading season was £184 plus VAT; £3/unit more than last year’s average of £181 plus VAT. This could be due to fewer purchasers in this category requiring entitlements for the lump sum exit support scheme, one of the key driving factors for prices in the Non-SDA market.

Graph J – SDA – all lot sizes – VAT and Non-VAT registered sales

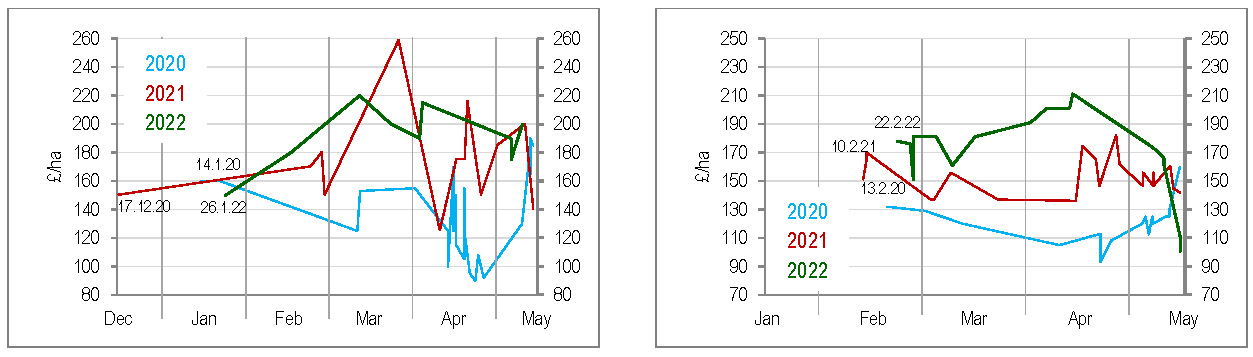

4.6 SDA MOORLAND

4.6.1 There were a large number of Moorland vendors with significant lot sizes in the hundreds, unfortunately there were initially few purchasers.

4.6.2 First sales were completed at £35/unit plus VAT with further sales ranging from £30 to £45/unit plus VAT.

Graph K – SDA-Moorland – all lot sizes – VAT and Non-VAT registered sales

4.6.3 In May the market picked up with several purchasers seeking large lots. All sales up to the deadline were fetching £40/unit plus VAT. However as trading closed there were still large lots left unsold as demand stalled.

4.6.4 The average price for the season was £40/unit plus VAT, down from £44/unit plus VAT in 2021. This represents a drop of 9% probably reflecting the lower return available from delinkage payments compared to Non-SDA.

4.7 LEASING

In 2022 we did not do any leasing as has been the case for several years, although there was some interest. We have found that RPA leasing has not proved to be popular since it was introduced in 2015, other than as a tool for a landlord to pass on entitlements temporarily to a tenant.

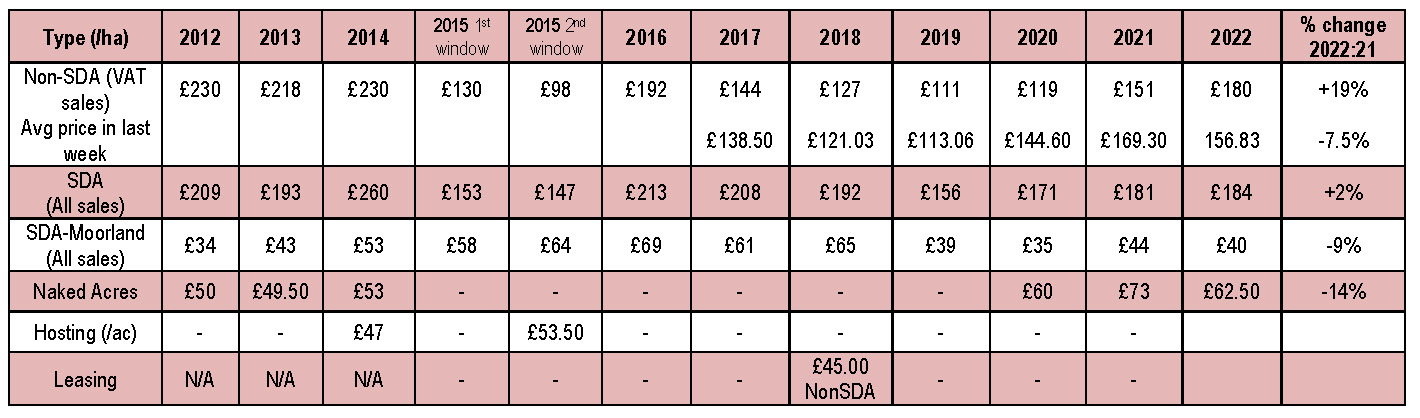

Table of comparative average sale and leasing prices for England

4.8 SCOTLAND

| Graph L – Region 1 – small lot sizes – all VAT & non-VAT registered sales | Graph M – Region 2 – all lot sizes – all VAT & non-VAT registered sales |

4.8.1 In Scotland, as with England, there are three different regions for entitlements, these being Region 1 (better agricultural land), Region 2 (rough grazing) and Region 3 (rough grazing with an LFA grazing category A). Whilst it appears that SGRPID will eventually replace BPS entitlements, at the time of writing it remains to be seen exactly how and when this will occur. The Agriculture (Retained EU Law and Data) (Scotland) Act 2020 provided powers to the Scottish Government to carry forward and eventually replace the current subsidy system. As such, BPS is expected to remain in place for at least a few more years.

4.8.2 There has been no siphon applied to the transfer of entitlements without land since 2019. The second and final instalment of the ‘convergence payment’ applied to 2019 and 2020 entitlements was paid in January 2021. This payment consisted of £160 million of CAP convergence payments, which were wrongly diverted from Scottish farmers in 2013. For 2019, £52 million of this fund was applied across BPS claims representing an additional £15.86 per unit for Region 1, £24.09 for Region 2 and £6.28 for Region 3.

4.8.3 Applications to transfer Scottish entitlements are made using either paper or email PF23 forms (dependent on the SGRPID office) sent to the SGRPID. The deadline for 2022 was 2nd April. Transfers are processed manually, which may result in a delay between submission of the application, and confirmation of transfer which usually comes in July, well after the claim deadline.

4.8.4 Region 1

4.8.4.1 The season started with high demand for Region 1 entitlements with several large lots sought. As the season progressed, there were many more vendors than purchasers and prices remained low.

4.8.4.2 Large sales for Region 1 entitlements were agreed in February and March at £150 plus VAT although very small lots fetched £170 to £210/unit plus VAT.

4.8.4.3 After the initial sales and throughout March, the price held at £150/unit plus VAT due to fewer purchasers.

4.8.4.4 The final week saw a high of £165/unit plus VAT. However, this season was characterised by low demand. Potentially this was due to large amounts of land being taken out of agricultural production for projects such as woodland creation or just a general uncertainty around the future of BPS. The average price for the season was £162.78/unit plus VAT, up on 2021’s average of £158.80/unit plus VAT.

4.8.5 Region 2

4.8.5.1 Similar to 2021 there was a slow start for Region 2 entitlements, with the first lots completed in March at £35 and then £40/unit plus VAT.

4.8.5.2 The last week of trading saw other mid-sized lots of Region 2 entitlements continue to be sold at £40 plus VAT with the price dipping as supply outstripped demand, sales were hampered by a lack of demand.

4.8.5.3 The average lot price sold in 2022 was £36.67/unit plus VAT compared to £37.50/unit plus VAT in 2021.

4.8.6 Region 3

4.8.6.1 Region 3 entitlements were in high demand this year with around 6,000 units sought at various points. There was however a lack of supply leading to few sales being completed. March saw prices for completed sales at £15 per unit plus VAT before the supply dried up.

4.8.6.2 The average lot size sold in 2022 was 660 units. The average price for the season was £15 plus VAT the same as in 2021.

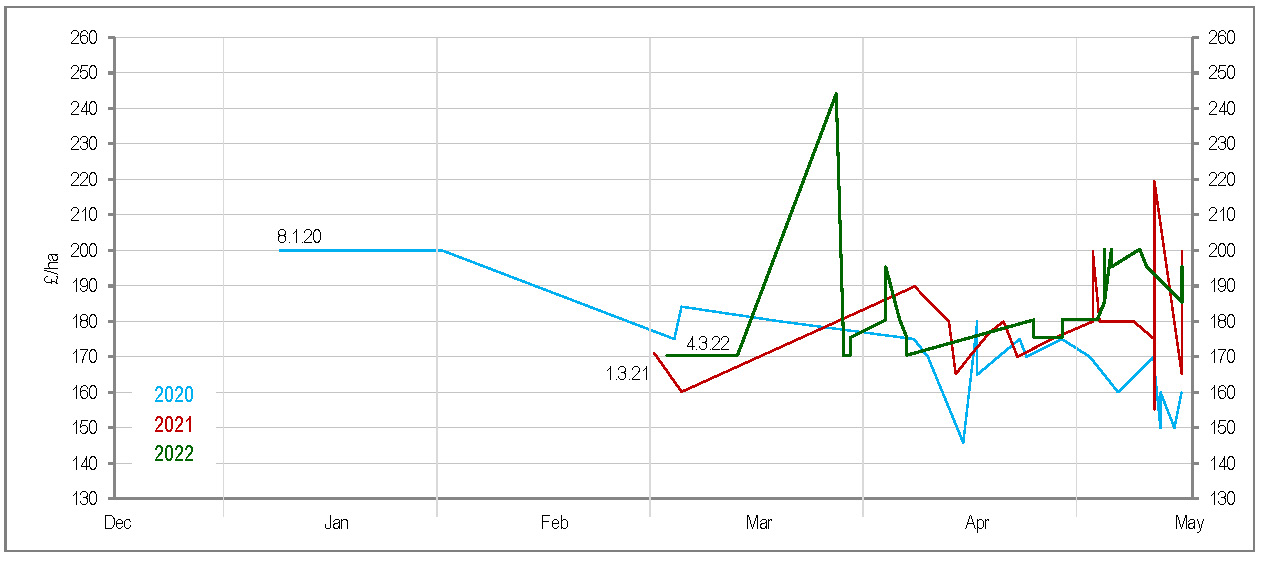

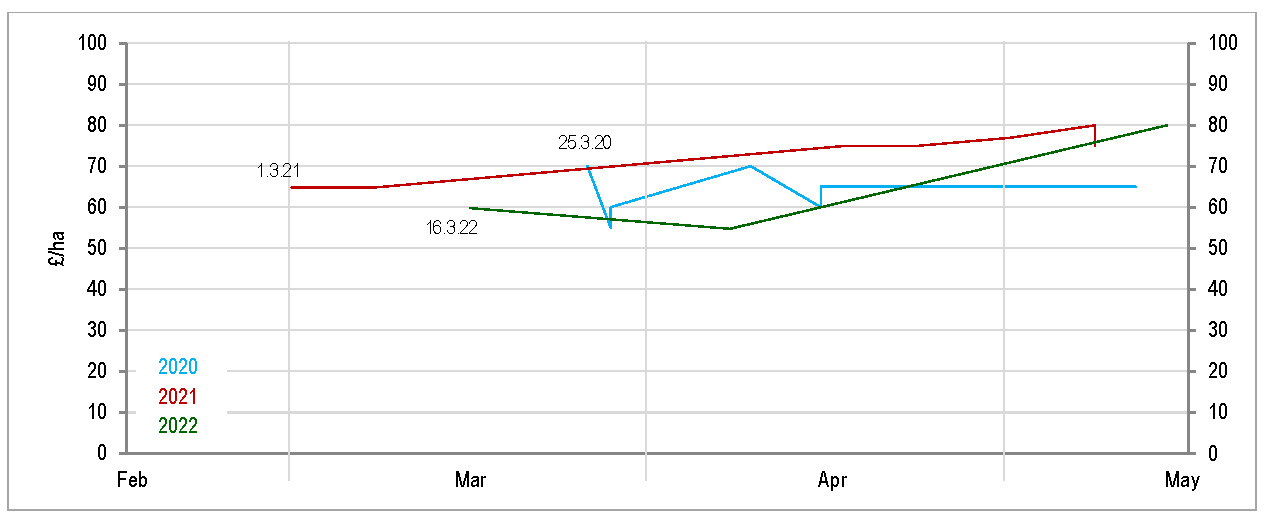

4.9 WALES

Graph N – 2022 Welsh entitlement sales – all lot sizes – VAT and Non-VAT registered sales

4.9.1 In Wales, the intention is that BPS will continue in the current format for at least one more year. The RPW have announced a ‘Sustainable Farming Scheme’ (SFS), part of the Sustainable Land Management (SLM) and is expected to be similar to ELMs in England, which will replace BPS. The SFS is expected in 2025 and as the Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) and Glastir payments are phased out the Welsh government will support businesses in the transition phase. It remains to be seen exactly what approach the RPW will take, whether phasing out entitlements or immediately removing the current system. There will be a ‘stability payment’ from 1 April 2025 to 31 March 2029 whilst the SLM and SFS are established although the exact details are yet to be formalised.

4.9.2 All land is classified as one Region, all Welsh BPS entitlements having the same flat rate value. On top of the flat rate there is also the Redistributive payment, unique to Wales, whereby the first 54ha of a claim attracts an additional approximate £92 per entitlement (subject to confirmation).

4.9.3 The deadline for submission of an online transfer application for Rural Payments Sales was 15th May, the same as the previous two years after it was extended due to the Coronavirus.

4.9.4 The Welsh market was especially quiet at the start of trading, we had vendors with large lots available from January but only small lots sought by purchasers. During March there were more purchasers, again for relatively small lots. This kept the market price at a stable £60/unit plus VAT.

4.9.5 During April prices fell slightly to £55/unit plus VAT. The market this year was characterised by high supply and few purchasers. The last few days saw prices rise to £80/unit plus VAT, but this was the high point of the season price wise. There was some interest from both vendors and purchasers in leasing throughout the season.

4.9.6 The average lot size sold through the trading period was 29.03. The average sale price in 2022 was £65 plus VAT, down by £8/unit from £73 in 2021.

4.10 NORTHERN IRELAND

4.10.1 DAERA have announced their BPS replacement scheme. The ‘Farm Sustainability Payment’ will be an area-based payment using existing entitlements and the current entitlement transfer system to sell, gift or lease entitlements. Other than the change in name there are a few tweaks to BPS; land must have cattle or sheep, pigs or poultry or at least 3ha of arable or horticultural crop. Land used solely for grass/silage production or with horses will not qualify. Payments will be reduced after a cap of £60,000 when they hit certain payment bands starting with 20% at £60,000-80,000 with the top band of between £150,000-£190,000 receiving an 80% reduction. There will be new Farm Sustainability Standards to comply with and participation in the Soil Nutrient Health Scheme and development of a Nutrient Management Plan also a requirement.

4.10.2 Northern Ireland entitlements are classed as a Single Region, but still have differing values depending on their historic element. Northern Ireland’s entitlements were supposed to move to a Flat Rate by 2021/2022 but this has not been implemented. Caution should be taken when purchasing as the FSP entitlements may not be the same value as BPS entitlements with an expected flat rate to be implemented.

4.10.3 Since 2021 the Greening payment was discontinued, the money paid out previously as part of this element has been incorporated into the flat rate value. Each entitlement’s flat rate therefore increased in value by around 43.6%, ensuring the same value was received for each claim as when greening was separate.

4.10.4 The deadline for submission of online (and paper) transfer applications was the 3rd May 2022.

4.10.5 As always there was higher demand than supply for Northern Ireland entitlements with purchasers from 2021 still requiring lots still sought on deadline day. As in the last two years they were available at face value throughout the season, price depending on an individual lots claim value. Lots were available at £250-265/unit plus VAT.

4.10.6 There was interest in leasing at around 50% of their claim value.

4.10.7 With all entitlements currently owned being used as like for like under the new FSP scheme this was reflected in the demand, there was confidence that any purchased this year would still be relevant in years to come.

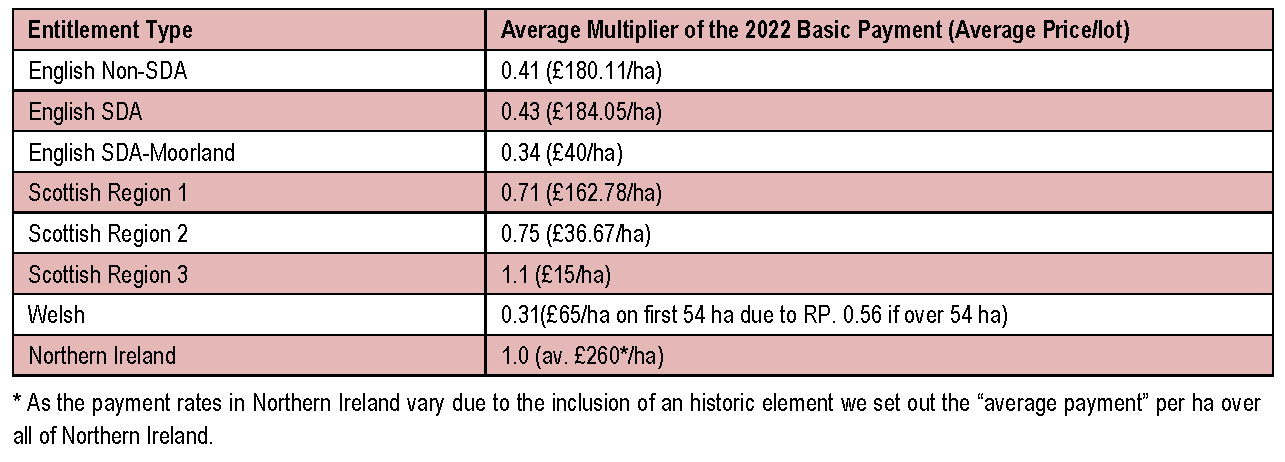

4.11 AVERAGE 2022 MULTIPLIERS OF MARKET VALUE v BPS PAYMENT RATES FOR ENTITLEMENTS SOLD ACROSS THE UK

4.11.1 We find it interesting to create a multiplier of the claim value per unit against the market value for each type of entitlement for each region. This allows us to compare the relative worth of purchasing each type of entitlement across the UK in terms of initial outlay to return. This is no longer a completely accurate reflection due to the differing approaches and timescales to phasing out BPS. Northern Ireland entitlements, for example, are expected to be around for several more years under a different scheme name whilst English entitlements were only worth this year’s and next year’s claim plus the delinkage payment.

4.11.2 English entitlements are again different from previous years in that in the past (and with the other regions currently) we would use one year of claim as the value for the calculations’ purposes. This year we will take both the current year, next year and the estimated delinkage payment to calculate what it is worth when purchasing an entitlement as anyone buying this year was doing so based on two full claim years and delinkage. Otherwise, claimants would have been paying more than they will receive back. The assumption is that each entitlement is part of a claim that makes up the lowest threshold of reductions (under £30,000), if the total claim is higher then the claim figures will be lower. Technically, to make this comparison fair, entitlements from each region should total all claims up to 2027 but we do not have exact confirmation on how each region’s entitlements will be dealt with going forward.

4.11.3 For example buying an English Non-SDA entitlement this year produces a Basic Payment of £186.57 this year, £151.59 in 2023 and an estimated delinkage payment of £97.17 (1/3 of 2021 base value multiplied by estimated reductions between 2025-27) if the total claim was under £30,000. If an entitlement was sold at £180.11/ha, this would mean it had been sold at a multiplier of 0.41 x face value (of the total payment).

4.11.4 The multipliers below are calculated based on the Basic Payment including Greening where appropriate and the Redistributive Payment (Wales only). The English values are based on a total claim under £30,000, over this amount the payment value of an entitlement would be reduced again.

4.11.5 For 2022, knowing the exact value of the English entitlements (assuming an individual’s claim is possible in 2023 as well), provides an accurate multiplier for the first time. The regions as in previous years, cannot be properly judged as it is impossible to know how many years a claimant will utilise the entitlements he has just purchased. This has, however, made it appear that English entitlements have a higher multiplier comparatively whilst they will technically be the lowest as they are the only ones with a confirmed end date. Of the rest, Welsh entitlements as always were the best value for money, costing less than a third of the annual payment for the first 54 units and a bit over half for any over this amount. Northern Ireland and Scottish Region 3 entitlements are again the worst value for money costing the same or more on average than their payment value. The Welsh ratio fell due to lower average prices whilst Scottish Region 1 were lower value year on year as their average price rose and 2 rose as the average price decreased.

5. WATER

5.1 UK WATER ABSTRACTION LICENCE TRADING – 2022

5.1.1 The trading and transfer of water abstraction licences is a specialist practice, and our team has years of experience in this area with ex-Environmental Agency employee experience. This combines with our valuation, expert witness and litigation expertise and the UK-wide market exposure only TCS Brokerage can offer with over 35 years’ experience of trading farm quotas/entitlements across the UK. There has been an intention for some time to reduce water abstraction rates across the country and the Environment Act provided additional powers to revoke or vary existing licences from 2028, at which point this may occur without compensation if deemed necessary to protect the water environment from damage or if there is a relevant environmental objective. A licence’s volume may be reduced if 75% or less is being used across the previous 12 years, although the reduction can only be to the amount that the holder reasonably requires.

5.1.2 Applying for a new licence, transferring or varying an existing one (except reducing volume, administrative changes, or transferring a licence from one person to another) involves paying an application charge based on the volume, water availability and type of licence. For example, an application for a new licence allowing groundwater abstraction up to and including 50 megalitres (50,000m3) a year within a ‘water available’ catchment would cost £2,150. The same quantity and purpose in a catchment with ‘restricted water’ may cost £3,662. If the volume was greater than 1,400 megalitres the respective figures would be £21,505 and £36,616. This by no means guarantees the success of an application, especially in ‘restricted water’ areas.

5.2 REGULATORY CONSIDERATIONS

5.2.1 Water abstraction (extraction) for industry, agriculture and drinking water, is regulated by the Environment Agency (EA) through the abstraction licensing system. Abstraction licence trading allows water users to buy or sell their water rights. This is beneficial because, with the exception of high-flow river water, no new licences are available throughout most of England and Wales. The only means of securing a new, year-round water supply is to purchase it from a water company, construct a storage reservoir, or to buy an abstraction licence.

5.2.2 Abstraction licence trades fall broadly into three types:

- ‘Water transfers’ where the abstraction licence is included within the sale of land.

- ‘Non-regulated trades’ where there is no requirement to change the terms or conditions of the licence, for example, supplying water by pipe to a neighbour to use for the same purpose.

- ‘Regulated trades’ where the point of abstraction or its purpose changes.

5.2.3 The EA has minimal involvement in licence ‘transfers’ or ‘non-regulated trades but will get involved in ‘regulated trades’.

5.2.4 In principle, the EA encourages licence trading because it allows them to allocate water resources to meet demand without issuing licences for additional water. They must however, meet the requirements of the Water Framework Directive which demands that abstraction is reduced in areas where water resources are under stress. Most of the rivers and groundwater supplies (aquifers) in the east and southeast of England are calculated to be under water stress with large parts of Wales, the southwest and north of England also affected. In an effort to return abstraction to sustainable levels the EA has recently started to use water trading as an opportunity to reduce licence quantities. This approach has suppressed licence trading activity in recent years.

5.3 RESTRICTIONS ON ABSTRACTION LICENCE TRADES

5.3.1 The EA divides England and Wales into 97 separate ‘water management catchments’. Each of these has a bespoke abstraction licensing strategy which sets out how water resources will be managed by the EA. Their approach to abstraction licence trading varies for each catchment according to local conditions but the same basic rules apply across the board:

- Trades must occur within the same waterbody and/or aquifer

- Surface water licence trades can generally only be made downstream

- Most trades are subject to a ‘sustainability reduction’ which removes any spare or previously unused water from the system.

- Changes in consumptive losses must be accounted for. (An irrigation licence returns less water to the environment than an equivalent vegetable washing licence. The increase in consumptive loss is deducted from the available quantity).

5.3.2 EA trading rules are becoming increasingly restrictive in the more water stressed eastern and southern parts of the country. For example, their Anglian Area trading policy issued in December 2020, applies a substantial ‘sustainability reduction’ to licence trades, requiring that the quantity available to the ‘donor licence’ is reduced to the average annual licence uptake between the years 2007 and 2012, before a trade can be considered.

5.3.3 The combined effect of sustainability reductions and the consumptive loss rule mean that there can be a significant difference between the amount of water stated on the licence and the amount available to trade.

5.3.4 Although the EA is taking steps to make licence trading easier with the introduction of temporary (rapid turnaround) trades, the limits on the spatial extent of potential trades and the risk of losing a large part of the licence has placed a strong chilling effect on regulated trading activity. Informal (unregulated) trades are, however, very common, particularly within the agricultural sector. Because of this informal nature, it is not possible to place a figure on the number of unregulated trades taking place, but industry experts estimate that up to 25% of agricultural abstraction relies on traded water.

5.4 ABSTRACTION LICENCE SALES UP TO 2022

5.4.1 With an especially hot dry summer, the drought-like conditions ought to create a demand for any available abstraction licences although it may also lead to the implementation of hands-off flow regulations to restrict abstraction.

5.4.2 We have seen trades for a variety of purposes in the lead up to 2022 including some 25,000m3 used for spray irrigation purposes and 90,000m3 used for trickle irrigation purposes being transfers between tenants.

5.4.3 There was demand from bottling companies, but proposed reductions of a surface water licence were not considered sufficient by the Environment Agency to compensate for the increase in groundwater abstraction, with further issues caused upstream of the proposed new abstraction point. As such this trade was rejected.

5.4.4 Negotiation advice for a further trade for bottling purposes was provided, which also looked at how to retain/obtain any rights granted to abstract water from the site.

5.4.5 Another approach involved a client actively seeking land to purchase which would have a pre-existing licence included as part of the sale. This would greatly increase the likelihood of a trade being approved.

5.4.6 Licences available included a licence for spray irrigation usage the volume of which was originally 159,000m3. It was especially pertinent to note the reduction in tradeable volume based on historic usage (also known as the ‘haircut’).

5.4.7 Further advice was provided on the value of a licence to establish whether a landlord should purchase the licence of an outgoing tenant along with the viability of any transfer. This was also affected by the historic usage of the licence effectively having the tradeable volume reduced to almost a fifth of the original volume.

5.4.8 One further licence had such a severe reduction in tradeable volume due to historic usage, going from tens of thousands to the hundreds, that the main objective of the client was to see how this figure could be challenged and a larger volume traded.

5.4.9 Demand continues to increase for licences in the South East with non-agricultural water users being prepared to pay £15 per cubic metre and agricultural users up to £10.

5.5 ABSTRACTION LICENCE ESTIMATED VALUE

5.5.1 The value of an abstraction licence can be broken down into its ‘asset value’ (the uplift in land or property value attributable to a licence) and its ‘use value’ (the amount a buyer will pay to use the water). It is difficult to get a ‘fix’ on market values due to the informal nature of most trades and the variations in local water demand and scarcity. ‘Asset value’ also varies according to the terms of the abstraction licence (including its expiry date and any constraining conditions) but as a rule of thumb, the increase in property value attributed to a licence is in the region of £10/m3.

5.5.2 Licence ‘use value’ depends largely on how the water is supplied. For agricultural irrigation in 2021, the ‘use value’ is approximately £0.50/m3 broken down as follows:

- Water right: £0.16/m3

- Supplied to field (pumps and pipeline) £0.17/m3

- Application as irrigation (including labour and machinery) £0.17/m3

5.6 LONG TERM PROSPECTS FOR ABSTRACTION LICENCE HOLDERS

5.6.1 The EA will continue to ‘claw back’ licences in over-licenced, water-stressed catchments in an effort to meet its 2027 Water Framework Directive sustainability obligations. Holders of existing ‘time limited licences’ are likely to take the brunt of these reductions although ‘non-time-limited’ and ‘grandfather rights’ type licences may also be affected in some water critical/high conservation areas such as the Norfolk Broads.

5.6.2 The UK Government is currently working on bringing the abstraction licensing regime into line with the Environmental Permitting Regulations (EPR). Although the effects of this are unlikely be felt on the ground before 2030, the EPR is likely to give the EA increased scope to address historic over-abstraction, particularly in the south and southeast. This will affect all sectors, reducing the quantity of water available to: public water supply, industry and agriculture. These regulatory factors combined with the reduction in summer rainfall expected with climate change will continue to put pressure on the UK’s water resources, driving up both the ‘asset value’ and ‘use value’ of sustainable abstraction licences into the foreseeable future.

5.6.3 Both the EA and Defra recognise the need to make better use of high flow and flood water and a new round of RPA grants for farm reservoirs and water management schemes has recently been announced. Support has also been provided by Government to help develop innovative, multi-beneficiary flood reduction and water supply schemes under the ‘flood and coastal resilience innovation programme’. It is likely that we will continue to see funding streams of this nature being rolled out over the next few years.