The new Biodiversity Net Gain market, contrary to early expectations, is a national market. Why this is and how it works is explained here.

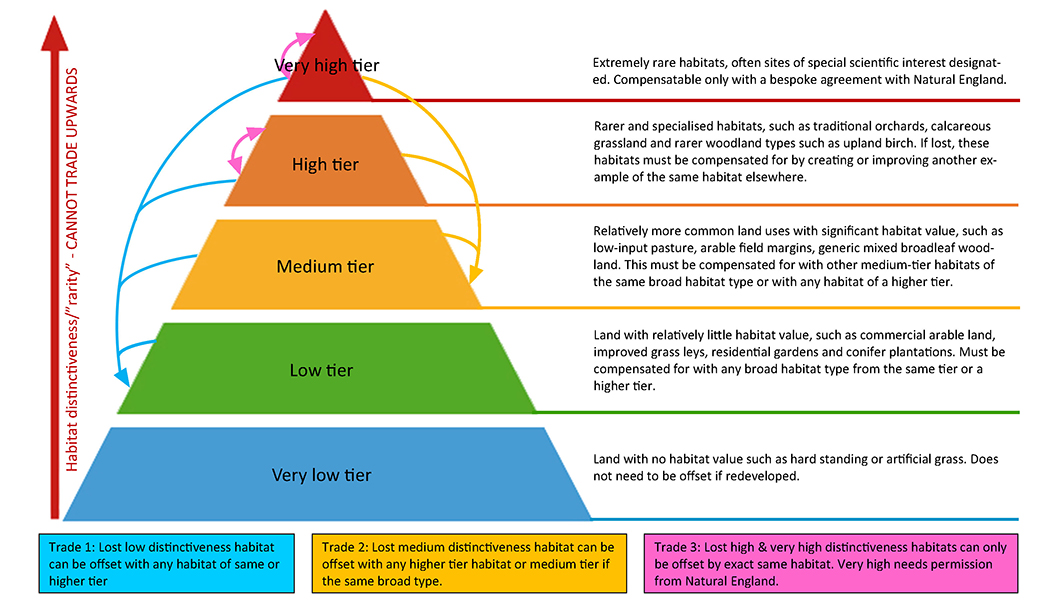

TCS Habitat Distinctiveness/”Rarity” and Trading Pyramid

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 One of the most common misunderstandings about the English Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) market is that the marketplace for any particular units created will be restricted to within the same Local Planning Authority (LPA) or the adjoining one. This confusion comes from two already well-known factors. The number of units sold outside their own LPA will be reduced by the “spatial risk multiplier” and developers are obliged to acquire compensation for lost units in the same LPA before they are able to buy units from further afield. If these were the only factors affecting BNG, the market would be similar to the Water Abstraction Licence market with hundreds of totally separate markets for each water catchment area.

1.2 However on closer inspection there are other factors that mean when looking at selling any BNG units one could be missing out on higher achievable prices if not offering them nationwide.

1.3 We are now familiar with exactly what BNG is aiming to be. BNG is the improvement in a habitat’s condition or the creation of new habitat to provide the equivalent of a 10% net gain in biodiversity value. If this cannot be achieved on the development site then developers may pay farmers and landowners to improve their land, this allows developers to meet what will become a statutory requirement for every type of development requiring planning permission.

1.4 However, there is some complexity as to how the different types of “net gain” compare with one another. Our Habitat distinctiveness/“rarity” Pyramid illustration above should be read from the bottom up.

2. TERMS

For the purpose of explaining BNG units, we will define the terms that are used. All habitats can be categorised by “broad type” and “distinctiveness”.

2.1 Broad habitat type

What the Government calls “broad habitat type” means the general category of land in question. There are 15 options for this in total, including woodlands, hedges, “cropland” (i.e. arable), grassland, urban, heathland, wetland, ponds, rivers and a few rarer options such as “sparsely vegetated land” and “intertidal hard structures”.

2.2 Habitats

Land within a “broad habitat type” can be one of a number of possible “habitats” which fall within the broad habitat type. For example, “grassland” as a broad habitat type includes, among other options, commercial ryegrass pasture (“modified grassland” in government language), semi-natural “lowland calcareous grassland”, and traditional hay meadows. Exactly which habitat is on a piece of land is set by the exact plants which are growing there.

2.3 Distinctiveness

2.3.1 Different habitats are split up by “distinctiveness”. This just means how rare and valuable the habitat is. Distinctiveness has five tiers, each represented by a layer of the Pyramid. Lower distinctiveness habitats are worth fewer BNG units and are simpler to replace; higher distinctiveness habitats are worth more units and the procedure for replacing them is more complicated. Habitats of different levels of distinctiveness are tradeable in different ways.

2.3.2 There are two ways a landowner can earn BNG units. One is to improve the “condition” of existing habitats. We do not cover this “improvement” here.

2.3.3 Alternatively new habitats that are of higher distinctiveness than the existing habitat can be created. What this means is moving the land from a lower tier of the Pyramid to a higher one. If you start with an intensive pasture field and stop ploughing and spraying it so it becomes an “unimproved” pasture the field will move up from the “low-distinctiveness” tier to “medium-distinctiveness”, which means you will have created units to sell.

2.3.4 Cannot replace a lost habitat with a habitat of lower distinctiveness

An important rule is that a lost habitat can never be replaced by habitat of a lower tier. In theory, if even a few square feet of mixed woodland, a “medium-distinctiveness” habitat, was lost to a development, the developer could not go ahead even if they committed to turning, say, all of a 30ha disused power station into a commercial conifer plantation (ignoring any of the broadleaf and open space areas which are always included in modern commercial planting). This is because commercial conifers, while more distinctive than the disused power plant, are less distinctive than the lost mixed woodland, so cannot replace it regardless of how much area they cover. They would instead in this example need to arrange for the planting, or improvement, of another woodland of medium distinctiveness or higher. It is not just a question of how large an area you replace a lost habitat with, but what distinctiveness the replacement is.

3. THE PYRAMID TIERS

The tiers of the Pyramid from bottom to top are:

3.1 “Very low” distinctiveness

3.1.1 These are areas which the Government does not think have any biodiversity value at all. Examples include AstroTurf, hardstanding and concreted areas. They have no value in terms of BNG credits – “Brownfield Sites”.

3.1.2 That means that they do not need to be replaced or compensated if they are lost when redeveloped and also that creating these areas will not gain you any biodiversity units. This appears logical – it seems absurd to create a new parking area or a modern farm building for wildlife reasons.

3.1.3 For example, if a developer were to build a new commercial building on the site of a recently disused petrol station, they may not need to purchase any BNG units at all because nothing of value is lost. No 10% net gain might be applied because 10% of zero is zero. However, there is also some government discussion about whether a set amount of net gain will be needed even under these circumstances.

3.2 “Low” distinctiveness

3.2.1 These are common land uses which the Government thinks have relatively little, but still some, value to wildlife. They usually represent land that is closely managed for the benefit of people living and working on it but also harbours some wildlife as an indirect result of this use. The most common are arable cropland, “improved” grassland (i.e. productive grassland that is frequently ploughed up, fertilised and/or reseeded), commercial timber plantations and residential gardens.

3.2.2 In practice, farmers are unlikely to produce many of these units. Almost all agricultural land will be low distinctiveness at a minimum. Therefore, there is simply not much scope for producing more of this kind of land for biodiversity, because most of the country is already at this distinctiveness or higher. The only way to create units of this habitat type would be something along the lines of taking up a hardstanding area and putting it back into cropping or intensive pasture.

3.2.3 When lost to a development, a low distinctiveness habitat must be compensated, but any other low distinctiveness or higher habitat will do, regardless of what kind. Any higher distinctiveness habitat can also be used, and this will quickly be worth more units than what was lost as lower distinctiveness habitats are worth fewer credits.

3.2.4 For example, if a developer wanted a residential development on an arable field (low distinctiveness), they may be able to make up a significant proportion of lost habitat just through the gardens of the houses in the new development. The remainder, plus the 10% net gain, might come, for example, from paying a livestock farmer to reduce their inputs on a few fields, turning these fields from improved to unimproved pasture. Because the unimproved pasture is a medium distinctiveness habitat, relatively little of this will be needed to make up for the loss of a larger area of arable cropland.

3.3 “Medium” distinctiveness

3.3.1 These are relatively common habitats which are frequently easier to establish than the higher tiers, while still being very important to the nation’s wildlife. They are enormously varied, covering some unusual land uses such as coastal silt and “green rooves” in cities. Some of the medium-distinctiveness habitats farmers are most likely to come across include “Stewardship-style” areas on arable land such as buffer strips and wildflower margins, “unimproved” pasture (i.e. not fertilised, ploughed or reseeded) that does not contain any particular rare plant life, most wildlife ponds, and many areas of planted amenity woodland.

3.3.2 Turning low distinctiveness land into habitats of this tier is likely to be the most common way for farmers to earn BNG credits. Those who have already been part of a Stewardship scheme will be familiar with many of the habitats which can be used, and actions such as digging a pond or committing to minimise inputs on grassland can, with adequate planning, fit into a commercial farming operation.

3.3.3 Broad types

Medium distinctiveness habitats are split up into several broad types. These include grassland, heathland, woodland, arable, inland water, coastal, urban and “sparsely vegetated” land. When medium distinctiveness land is lost to a development, it must be replaced with either other medium-distinctiveness habitats of the same broad type, or any habitats of “high” or “very high” distinctiveness.

3.3.4 This means that if the residential development mentioned above included building on what is currently a wild bird seed mix, the developer would need to offset this by paying for either other medium-distinctiveness arable habitat or any high or very-high tier habitat to be created or improved. This means the developer could use units from a new buffer strip or wildflower margin, but they could not use units from someone reducing fertiliser inputs to create semi-natural grassland, because this is a different broad type of habitat in the same tier. They could, however, pay for creation or improvement of a traditional hay meadow, because although this is of a different broad habitat type it is also a very high distinctiveness habitat. They could also not use units from someone turning a disused car park into productive cropland, even though this is the same broad type of habitat, because the resultant cropland would be of lower distinctiveness than the lost seed mix. In essence, a lower tier of the pyramid can never compensate a higher one.

3.4 “High” distinctiveness

3.4.1 These are rarer and very valuable habitats which are generally difficult to replace if they are lost. Although varied, there are actually relatively few of these kinds of habitats affecting farmland, not least because no arable habitats are considered any higher than medium distinctiveness. Perhaps the most significant are various types of relatively rarer woodland, for example lowland deciduous and native pine. Others to note include upland calcareous grassland and “tall grassland herb communities”, most open heathland, wetland reed beds and many inland water features including reservoirs, lakes and more ecologically important wildlife ponds.

3.4.2 Most of these habitats are difficult for farmers to create, with the two grassland habitats in particular unlikely to be feasible in most circumstances (some very high distinctiveness grassland habitats are likely to be easier to establish). However, those engaging in woodland planting could aim for a woodland from this tier, and an ecologically important wildlife pond is something a farmer in a priority location could potentially create. A heathland farmer could likewise create open heathland by sympathetic scrub clearance.

3.4.3 Replace with exact same habitat

Where a developer is building on a high distinctiveness habitat, they must replace it with the exact same habitat elsewhere. In other words, if they have somehow gained permission to fill in a high-priority wildlife pond as part of their development, they must ensure another such pond is created (or improved) elsewhere before they can proceed. It may be that for some habitats in this tier, very few credits are available as few farmers can create these habitats, so the credits could be very valuable indeed to a developer requiring them. However, biodiversity offset is in addition to, rather than in replacement of, other planning constraints. Developers may find it difficult to receive permission to build on them before BNG is even considered, especially as many of these kinds of habitats will be found on protected sites such as National Parks, nature reserves and SSSIs. They are also largely quite rare, meaning there are relatively few of them to develop on in the first place. Therefore, whilst supply of credits may be limited, demand may be limited even more. However, where a farmer can create a high- rather than medium-distinctiveness habitat, other factors such as cost being equal, they still should consider this. Even if they cannot find a buyer for that exact habitat, the higher distinctiveness means they should have more credits to sell to buyers wanting medium-distinctiveness habitats, or lower distinctiveness habitats in general. These credits will also be more versatile because they are not limited to a single broad type of medium-distinctiveness habitat, likely making them more valuable.

3.5 “Very High” distinctiveness

3.5.1 These represent what are, in theory, the rarest and most valuable habitats in the country. They range from the highly specialised, such as “littoral seagrass on peatland” to the surprisingly familiar “meadows”. The latter category includes traditional hay meadows which can conceivably be created, albeit with some effort, by a livestock farmer moving to a less extensive operation. “Wood pasture and parkland” and “traditional orchards” are also both included and are relevant to many traditional estates as well as farmers experimenting with agroforestry. Other habitats in this tier which might be found on-farm include lowland dry acid grass, purple moor grass (known in Devon as “Culm grass”) and all kinds of peatland.

3.5.2 Under the new rules, developers will require special permission from the Secretary of State before they can build on these kinds of habitats, which will require a specially tailored compensation strategy. This is, we think, likely to be prohibitive even to the largest private developers. However, it may arise in relation to some national infrastructure projects. This means the market for these units is likely to be very small, but they will be extremely valuable to those that require them. Note that because the tier below this, “high distinctiveness” requires like-for-like replacement, these credits can only be traded down for medium and low-distinctiveness offsetting. However, creation of these habitats has the potential to produce so many units that, once again, it is worth seriously considering creating these where possible compared with other tiers.

4. SUMMARY

4.1 The meaning of all this is that we now have some understanding of how the national BNG market will work in practice and that some expertise will be needed to operate efficiently in it.

4.2 Developer demand for low distinctiveness (LD) credits will represent a floor price. We think most credits farmers create will be medium distinctiveness (MD) of one kind or other. When there is no demand in their area for the specific type of MD credit a farmer has created, they can sell their credits on the LD market instead to receive some profit. If there was more demand than supply for all types of MD credit, the LD price will tend to match whichever MD credit is the least expensive.

4.3 MD credits will, for their part, have their markets split by type. The most commonly produced, and most in demand, will be medium distinctiveness grassland (MDG) and medium distinctiveness arable (MDA). This is because farmers will find these kinds of credits easiest to produce, and also because developers are most likely to develop this kind of land. However, there will also be markets for medium distinctiveness heathland (MDH) in the parts of the country where it is relevant, medium distinctiveness water (MDWa) where a pond must be filled in for a development, and medium distinctiveness woodland (MDWo) mostly for infrastructure projects because planning permission for housing or commercial use is rarely granted on established woodland. Urban, intertidal and “sparsely vegetated” land will also each have their own MD markets. These will be more specialised, so relevant to fewer farmers, but those who do farm along coastlines and river estuaries, or in areas with exposed rock, would perhaps do well to take note.

4.4 High distinctiveness (HD) and very high distinctiveness (VHD) will contain within them a “micromarket” for each specific habitat, with both buyers and sellers sometimes waiting for long periods before being able to do high value trades. We think they will behave in a similar way to the water abstraction licence market, in this sense. However, we also expect that sellers in the top two tiers will frequently prefer to save themselves the time and complexity and sell their credits on the LD or the MD market instead. This may mean very rich rewards for those who wait!

4.5 Therefore this illustrates why the marketing of BNG units should always be carried out nationally as distinctiveness can make units in one LPA that much more valuable than in another even having taken into account the reduced number that can be sold.

Download/view Fact Sheet 15 here